Mai Meksawan worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival since 2004, and was its programmer until the festival’s final edition in 2009.

...01 Jan 2025, 22:47

This content isn't available at the moment

When this happens, it's usually because the owner only shared it with a small group of people, changed who can see it, or it's been deleted.20 Jul 2023, 20:23

www.nyaff.org

Tickets go on sale this Friday at 12pm ET for the 22nd edition of the New York Asian Film Festival (NYAFF), presented by the New York Asian Film Foundation and Film at Lincoln Center (FLC), running fr...29 May 2023, 15:15

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell — Cercamon

www.cercamon.biz

After his sister-in-law dies in a freak motorcycle accident in Saigon, Thien is bestowed the task of delivering her body back to their countryside hometown. It is a journey in which he also takes his ...

Mai Meksawan worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival since 2004, and was its programmer until the festival’s final edition in 2009.

...

EVERY DAY A GOOD DAY is about a young woman’s induction into Japanese Tea ceremony over two decades. The movie is delivered

...

Hazel Orencio is a Filipino actress discovered by Lav Diaz in 2010. Her filmography includes Florentina Hubaldo, CTE (2012), Norte, The End

...

Mostofa Sarwar Farooki is a filmmaker and producer from Bangladesh. His first international breakthrough took place in 2009 with Third Person Singular

...

« Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains » (富春山居圖), Gu Xiaogang’s beautiful first feature film, which premiered at Cannes International Critics’ Week in

...

Thinley Choden is a producer and social entrepreneur from Bhutan. Her first film project was the Emmy Award winning documentary Bhutan: Taking

...An independent arthouse movie theater with two screens since 1980, the Espace Saint Michel, in Paris, facing the famous Saint Michel fountain in the heart of the Latin Quarter, is run by the Gérard family across generations since 1912 –when Claude Gérard’s great-great uncle turned a popular restaurant into a cinema.

Claude Gérard is the current owner and director of the cinema – a fiery outspoken iconoclast who shares with us his mystical attraction for Asian cinema while standing up for an eclectic editorial line that puts emphasis on discovery and focuses on world cinema and political filmmakers.

Which was the most successful Asian film at Espace Saint Michel?

Following the 1988 arson attack that hit the cinema, we reopened in 1991 with the beautiful film DEATH OF A TEA MASTER (千利休 本覺坊遺文) by Kei Kumai – a Japanese filmmaker unknown to the French public at the time. The film, however, hit 2,500 admissions in just one week! Today it would hardly reach 500 admissions. Quality films are rare – and when they manage to be produced, they are lost in a flood of bad films. In an effort to trivialize and popularize cinema (with the help of digital technology), we are now overwhelmed by poor quality films… It’s a problem because people are getting disgusted with the mainstream film offer that leaves little space for smaller films they are no longer aware of.

At my father’s time, the arthouse market was not as segmented as it is today; there were only good films! In the Latin Quarter neighborhood, the Champo cinema stands out because it’s just next to La Sorbonne university and has become a cultural reference. They show 20 to 30 films per week, which is fine. But as far as I’m concerned it’s not how I want to show films because I’m interested in discovery.

What is the first Asian film you ever saw?

By the age of 7, I was very impressed by GATE OF HELL (地獄門) by Teinosuke Kinugasa (Grand Prize at Cannes Film Festival in 1954). There’s an incredible scene where the samurai spits on her beloved’s face to revive her! I reenacted the scene every summer at the beach! [Laughs]

Do you feel accountable for the way the audience of the cinema view Asia? Does that impact your programming choices?

Of course but it’s not just about Asian cinema. As I said before, quality films are what drives me. I do specifically have a liking for Asian cinema though – from South Korea, Japan, Iran… I can’t really explain. I used to go to the 3 Continents Festival in Nantes, where I identified films that unfortunately wouldn’t always make it to French movie theaters because no distributors would acquire them. At the end of the day, my only responsibility is to show quality films and favour new talents from any part of the world. Not so long ago, I programmed for instance HONEYGIVER AMONG THE DOGS (Munmo Tashi Khyidron) by Bhutanese director Dechen Roder.

Why were you specifically interested in that film?

Curiosity! Nowadays, everybody travels but everybody goes to the same places. It’s not curiosity, it’s mundanity. Curiosity is straying from the beaten tracks, it’s looking into seeing what others don’t.

GATE OF HELL aside, which Asian films struck you most?

I was very impressed by ONIBABA (鬼婆) by Kaneto Shindo as well as WOMAN IN THE DUNES (砂の女) by Hiroshi Teshigahara – I just find the direction, the images, outstanding. In fact, it’s impossible to describe. It’s better to watch the films, some things can’t be explained. I don’t like film reviews. Cinema is about sensibility, aesthetics, a perception of beauty. We tend to intellectualise when we grow up. But we must go to the movies with the sensibility, the innocence, of a child.

Interview by Françoise Duru and Pauline Kraatz

Technical specifications

Espace Saint Michel

7 place Saint Michel – 75005 Paris – France – T +33 (0)1 44 07 20 49 – www.espacesaintmichel.com

Art & Essai and Europa Cinemas labels

Exhibition formats: digital, 35mm, 4K

2 screens: 120 seats (screen width 7.20 m) and 90 seats (screen width 6.50 m)

Bar Les Affiches: open from Tuesdays to Saturdays from 18:00 to midnight

Asian film with the most cinema admissions: DEATH OF A TEA MASTER by Kei Kumai (12.425 admissions)

ABOUT THE ESPACE SAINT MICHEL

Born in 1945, Claude Gérard was steeped in cinema from an early age. The movie theater was founded by his great-great uncle, Victor Gandon, in 1912. Living in the neighborhood, Claude would never miss a film screened by the family cinema -then a single-screen theater with 450 seats (including orchestra and balcony) following the transformation works carried out in 1925 by his grand-father, Gaston Gérard.

Claude’s favorite seat is the orchestra front seat: he wants to feel immersed in the film and fill his visual field with the moving images. He keeps fond memories of his first cinematographic emotions like when he first saw THE INDIAN TOMB by Fritz Lang in 1959.

Later, while pursuing his studies at HEC Graduate Business School, he prepared the entrance exam for film school IDHEC (now called Fémis) at Nanterre University where he studied under Jean-Pierre Melville (who was shooting ARMY OF SHADOWS). It was a time where he would also cross on campus the paths of likes of “Dany le Rouge” (Daniel Cohn-Bendit’s nickname).

But the May 68 events put an end to his film studies as all exams got cancelled and he eventually gave up the idea of becoming a filmmaker. He then became his father’s assistant and slowly took over the cinema in 1991, which benefited by then from a second screen since 1980 (the balcony of the single-screen cinema had been replaced with a second screen).

As of 1970, the Espace Saint Michel was fully exposed to the intense competition of the Odeon cinemas (UGC with 9 screens and Parafrance with 5 screens), the multiplexes’ ancestors. While it was easy to book the films in the past, it had become a tough challenge. Negotiations with distributors would become fierce as theater programmers all wanted the same film or all rejected the same film. That’s maybe what made the Espace Saint Michel an alternative political space… In 1974, few movie theaters were willing to book BREAD AND CHOCOLATE by Franco Brusati, deemed « too communist ». In 1988, that spirit of freedom came under the fire of an extremist catholic cell that set ablaze the movie theater because they were angered with the programming of Martin Scorsese’s LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST. The cinema will only reopen in 1991, with an additional space called « the club » dedicated to Q&As and special events.

In 2016, THANKS, BOSS! by François Ruffin was side-stepped by several movie theaters for political reasons but was welcomed with open arms by the Espace Saint Michel… Impertinence and activism has certainly remained the trademark of the programming at Espace Saint Michel.

Over the course of his forty-year career, Claude Gérard reckons that the public is what changed most: the viewers used to be young and curious, they are now older and overwhelmed by blockbusters and commercial films with questionable quality. Genuine cinephiles are rare, especially in this neighborhood crowded with tourists that used to be at the crossroads of two worlds – the 6th arrondissement middle-class and the grands boulevards working class. « In the 50s, we sold up to 11,000 tickets per week. In 2019, we celebrate over champagne when we sell just 1,000 tickets… » Claude Gérard laments… and simultaneously gets passionate: « Curiosity will come back, people will end up revolting against brainwashing. »

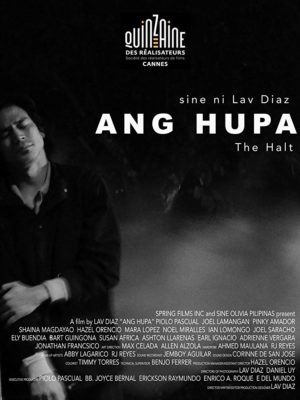

In 2034, after massive volcanic eruptions in the Celebes Sea, the sun has permanently set, plunging Southeast Asia into darkness. Madmen control every country, city and enclave. Epidemics have ravaged the continent, leaving millions dead and forcing the survivors to flee.

Presented at Cannes Directors’ Fortnight, THE HALT demonstrates once again the prolific creative energy of Filipino director Lav Diaz (SEASON OF THE DEVIL, THE WOMAN WHO LEFT, DEATH IN THE LAND OF ENCANTOS…) in the service of a political thought always on the move. Resorting to the codes of the genre film, he denounces abuses of power and questions individual action.

THE HALT

(Ang Hupa)

A film by Lav Diaz

With Piolo Pascual, Joel Lamangan, Shaina Magdayao

With Piolo Pascual, Joel Lamangan, Shaina Magdayao

2019 – Philippines – Science fiction, Drama – 279 min – 1.85:1 – 5.1 Sound – Tagalog

| Screenplay: |  (4.0 / 5) (4.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (4.0 / 5) (4.0 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

Surrounded by the Philippine Sea on its Eastern coast, the South China Sea on its western coast and bounded by the Celebes Sea on the south, the Philippine archipelago is more commonly situated in the Pacific Ocean. The Philippines consists of at least 7600 islands – 2,000 of them officially inhabited – covering a total area of about 300,439 km2 (or 120,000 sq mi). Many of those islands are actually islets, the eleven largest islands alone accounting for more than 95% of the surface area. In 2017, the total population was estimated at about 104 million. Today, the Philippines is separated into three archipelagos (Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao) and seventeen distinct regions, with relatively restricted autonomies. There is one exception: the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), which, in the context of a prolonged religious and geopolitical crisis, possesses a specific status.

Originally made up of different populations originating from different immigration waves from the Asian continent, the Philippines is the only country in South East Asia that was colonized before even having the time to develop a centralized government or establish a dominant culture.

Not long after the arrival of a Spanish expedition led by the explorer Ferdinand Magellan, in the sixteenth century, the Philippines consisted of dispersed tribes, often polytheist, of Chinese settlements/communities, resulting from frequent commercial exchanges with the mainland, and of sultanates, under the influence of neighboring Indo-Malay maritime kingdoms, that had started to spreading Muslim precepts.

The arrival of the Spanish changed this situation through and through. The first permanent Spanish colony was established in Cebu in 1565. Manila was founded in 1571 and, by the end of the sixteenth century; almost all of the archipelago was under Spanish control. The priests had by then started converting the natives to Roman Catholicism. Were left the Muslims of Mindanao and Sulu, called “Moros” by the Spanish, who resisted and fought against this foreign domination. During this period, State and Church were the pillars of the Spanish administration, the objective being both commercial and cultural. In particular, the Spanish clergy set out to Christianize and hispanize the local peoples, banning native religious and cult practices.

The implemented agricultural policies and land laws reinforced class divides, enriching the aristocracy and new land owners to the detriment of the farmers.

The acceleration of unrestricted trade with Europe and the establishment of harbors open to international commerce saw the rise of a new wealthy social class, related to the Sino-Filipino merchant communities.

Around the 1880s, many of their children were sent to study in Europe. This led to a growing penchant for nationalism and reformism, materializing in the propaganda movement of Filipino students in Spain, led by a brilliant student, José Rizal, the author of two exemplary political books – Noli me tangere (1886) and El Filibusterismo (1891) – which have had a tremendous impact back in the Philippines. Once he returned, he founded on July 3, 1892, the Filipino league, an organization that sought to promote liberal and reformist ideas. He was rapidly arrested, made to appear in front of a bogus court and was eventually executed on December 30, 1896, at only 35 years of age. He instantly became a martyr and his death bolstered the resistance.

Inspired by Rizal’s writings and shocked by his arrest, Andres Bonifacio advocated for a general insurrection through the Katipunan, a secret society created to free the country from its Spanish colonizers.

The reasons that led to the split of the Katipunan in two rival factions have been the object of many diverging/contradictory theories. What is certain is that this divide placed the Magdiwang group (led by Bonifacio) in opposition to the Magdalo group (which wanted to place Emilio Aguinaldo at the head of the movement). Meanwhile, the Spanish troops progressed rapidly.

On March 22, 1897, a reunion – known under the name of “Tejeros convention” – was called at Cavite to solve the issue of the political direction of the revolution. Once again controversy permeated the discussions, at the end of which were born two opposing revolutionary governments: one controlled by Aguinaldo, the other by Bonifacio. The rivalry between the two men reached a climax when Bonifacio was imprisoned by Aguinaldo’s soldiers and, after having been found guilty of treason, was executed on May 10, 1897 in the mountains of Maragondon.

Many discouraged partisans abandoned the cause and gave up armed struggle. On December 14 and 15, 1897, the rebel troops of Aguinaldo surrendered and the Biak-na-Bato pact was signed: Aguinaldo obtained amnesty for all of the Katipunan’s members but the leaders were forced in exile to Hong Kong (an exile that was financially compensated…).

The explosion and sinking of an American warship in Havana in February 1898, during a Cuban revolution, contributed to the United States declaring war to Spain two months later, which in turn favoured the return of Aguinaldo and reinforced the Filipino rebellion. The Spanish were forced to sell their colony to the United States for 20 million dollars and leave the country, after signing the Paris Treaty on December 10, 1898.

Aguinaldo had in the meantime declared the country’s independence, on June 12, 1898, at Cavite. This was the establishing act of the first Philippine republic, the first democratic constitution of the Asian continent, after 327 years of Spanish domination. It became clear however that the Americans had no intentions to leave or grant autonomy to the Filipino people. On February 4, 1899, war was declared between the two. This rebellion was hastily crushed by the Americans in 1902, following Aguinaldo’s capture. The Americans ruled the country until the Japanese invasion of 1942. The Allies won back the islands in 1945 and the United States administered the country until its independence, appropriately proclaimed on July 4,1946.

Under American influence, the English language exceeded the local dialects and the political organization was modeled on the American system. Land ownership remained very unfair, favoring the richer, more politically connected parts of society, all the while serving American economic interest.

Originally made up of different populations originating from different immigration waves from the Asian continent, the Philippines is the only country in South East Asia that was colonized before even having the time to develop a centralized government or establish a dominant culture.

In November of 1965, Ferdinand E. Marcos was elected president. His administration was confronted to serious economic problems, exacerbating issues of corruption, fiscal evasion and smuggling. Facing the increasing importance of demonstrations – notably led by students – that demanded more transparency and the transformation of institutions, Marcos declared martial law in 1972 – officially, a drastic measure seeking to put an end to the alleged threats of the new Communist party and the separatist Muslim movement, but, in realty, a means to modify the institutions and assure the longevity of his mandate. One of the first measures taken was the arrest of his political opponents. In the South of the country, the separatist rebellion became more and more galvanized to act.

Under Martial law, urban crimes plummeted, unregistered weapons were confiscated but the political and economic hold of Marcos and his associated on the country was consolidated, against a backdrop of widespread corruption and contempt for the collective interest.

In 1986, Corazon C. Aquino, the widow of Benigno Aquino, one of Marcos’ political rivals who had been assassinated in 1983, became president, helped by the popular feeling of incrimination towards Marcos. She re-established a form of bicameral government as it had existed before the martial law. However, the external debt soared, the country’s economy remained in a dire stare and the menace of Moro and communist uprisings was still very real. The Aquino government was also confronted to internal dissension, repeated coup attempts and natural disasters. At the beginning of the 90s, criticism of weak leadership, corruption and human rights abuses were on the rise. In 1992, Aquino renounced to present herself as a candidate for a second term.

Following this, several presidents – all originating from the elite and important families – succeeded one another, without ever managing to put a term to inequalities or to accusations of corruption, while the conflicts with the separatists in Mindanao carried on (amounting to over 120,000 victims and about 2 million displaced over the course of 40 years). In November 2013, the Haiyan typhoon, one of the most violent ever felt – struck the country.

On May 9, 2016, Rodrigo Duterte, the long-time ruling mayor of Davao was elected president, despite (or thanks to?) his populist rhetoric, making a vow to execute 100,000 criminals. During his inauguration in June, the unlawful killings of suspected drug trafficking criminals leaped, without any trial in sight.

In May 2017, Duterte declared martial law on the island of Mindanao to circumvent the islamist and communist rebellions. Initially decreed for 60 days, the parliamentarians validated its extension at his request. This exceptional regime is an extremely sensitive matter in the Philippines, as it recalls the dark times of Marcos’ dictatorship.

Duterte, who has rehabilitated Marcos by authorizing his burial at the national heroes’ cemetery, had threatened to extend the martial law to the entire country if the islamist threat were to export itself to other regions.

Human rights organizations, which have repeatedly denounced the president’s aggressive campaign against drugs, accuse him of endangering the Filipino democracy, three decades after the revolution that drove Marcos out of power.

Tonglao S. Epinal

Tonglao S. Epinal is a photographer and a video artist. She collaborated with many specialized magazines as a freelance writer and frequently travels to South East Asia for her works and research. She is currently developing a documentary feature about the heritage of Soviet cinema and the paradox of censorship in the development of Asian arthouse cinema from 1956 to 1986.

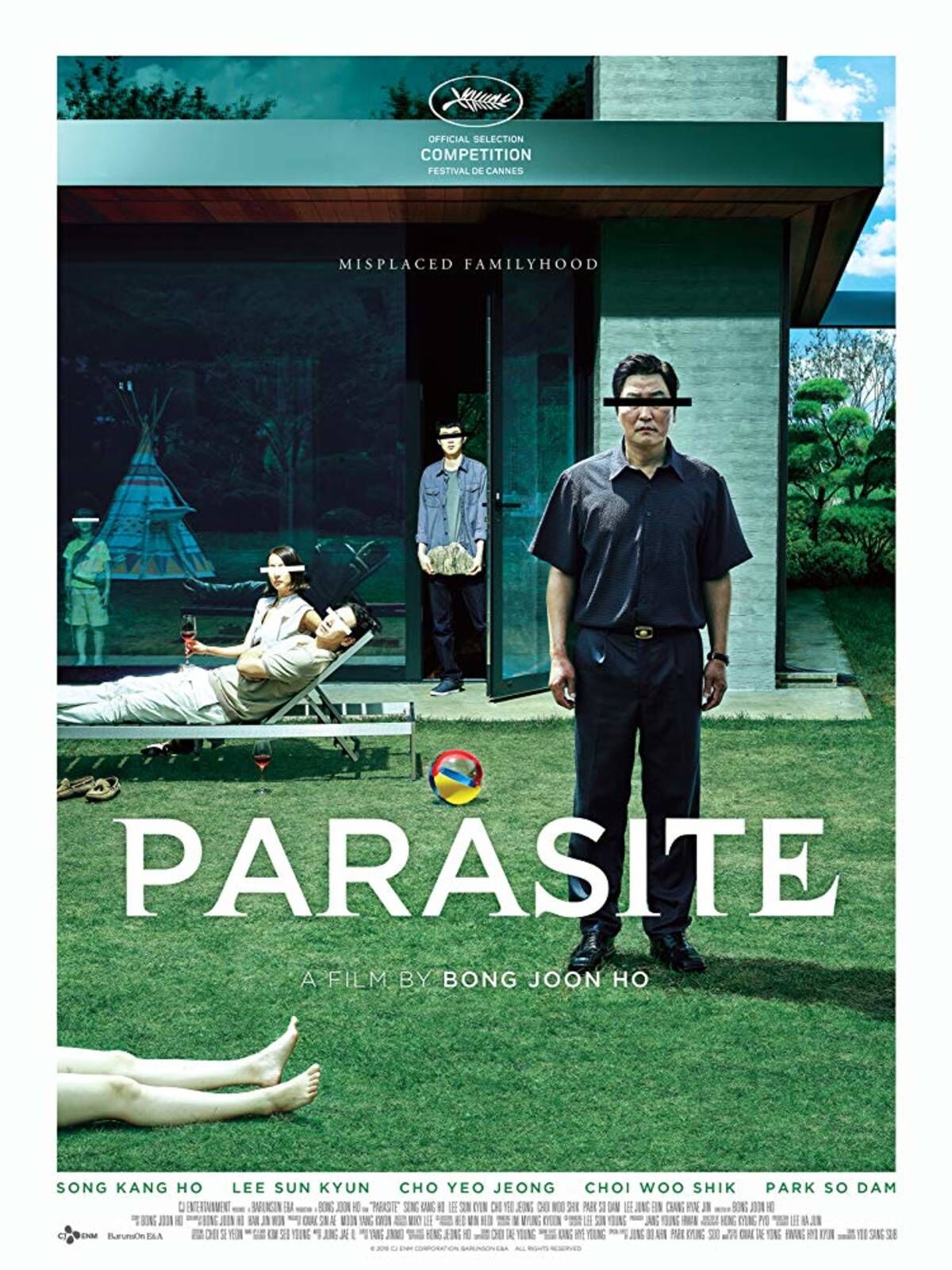

(3.8 / 5 After SNOWPIERCER and OKJA, South Korean director Bong Joon-ho pursues his malicious taste for excess, providing with PARASITE a hyperbolical social fable, as caustic and exhilarating as can be! An audacious move, well rewarded by the Alejandro González Iñárritu-led Cannes jury. )

(3.8 / 5 After SNOWPIERCER and OKJA, South Korean director Bong Joon-ho pursues his malicious taste for excess, providing with PARASITE a hyperbolical social fable, as caustic and exhilarating as can be! An audacious move, well rewarded by the Alejandro González Iñárritu-led Cannes jury. )After presenting MOTHER at Un Certain Regard in Cannes in 2009, South-Korean director Bong Joon-ho returns with a bang for PARASITE, an eccentric social satire. Featuring the imposing Song Kang-ho, noticed in MEMORIES OF MURDER and THE HOST by the same director (as well as JSA and SYMPATHY FOR MR. VENGEANC by Park Chan-wook), the film has earned the Palme d’Or, and unanimous praise.

PARASITE

(기생충, Gisaengchung)

A film by Bong Joon-Ho

With Song Kang-ho, Lee Sun-kyun, Cho Yeo-jeong, Choi Woo Shik, Park So-dam, Chang Hyae Jin

With Song Kang-ho, Lee Sun-kyun, Cho Yeo-jeong, Choi Woo Shik, Park So-dam, Chang Hyae Jin

2019 – South Korea – Thriller, Comedy– 131 min – 2.35:1 – Dolby Atmos sound – Korean

| Screenplay: |  (4.0 / 5) (4.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (4.0 / 5) (4.0 / 5) |

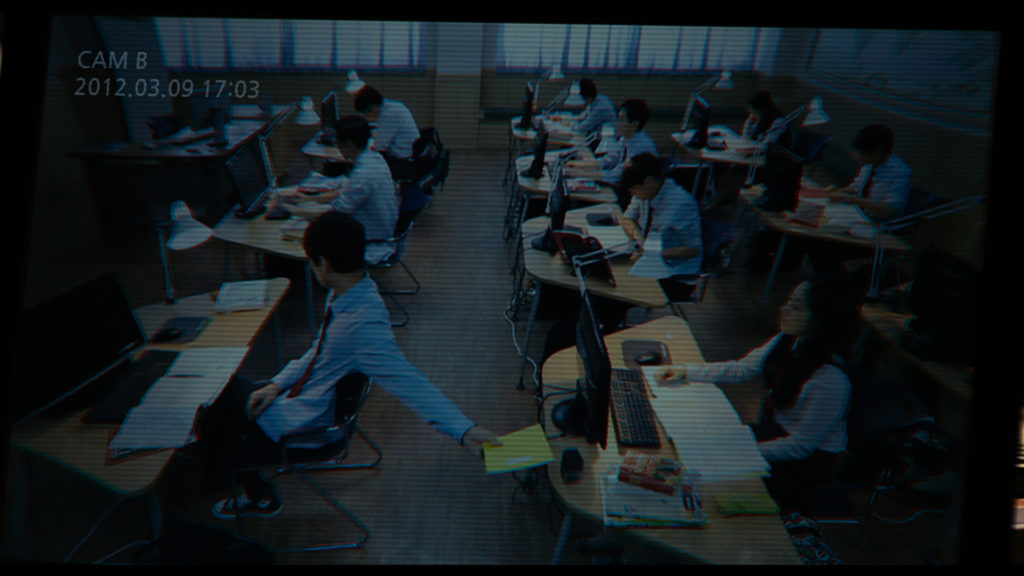

“Radical self-love and acceptance” – all the rage in western societies- hasn’t quite reached South Korea. A Korean’s self-worth is first and foremost defined by others’ judgment, in turn directly determined by one’s Suneung results. This national exam can make or break a reputation and a bad score can become a lifelong, sometimes fatal, stigma. Bong Joon-Ho gets down and dirty in PARASITE and taunts – through the characters’ outrageous attitudes which lead to a downward spiral – the weight of this ‘rite of passage’. In a more matter-of-fact way, Marie-Orange Rivé-Lasan and Jin-ok Kim reveal the underpinnings of the Suneung, which produces extreme and sometimes-bleak consequences.

The term « Suneung » is an abbreviation of the expression « suhak neungnyôk sihôm » which literally translates to « aptitude studies test », the unavoidable end of studies exam preceding university in South Korea. This decisive test doesn’t only attest to a specific level of competence, it also (and especially) generates a national ranking of all the candidates. According to this ranking, the candidates may apply to different universities. Universities are nationally classified: the higher they rank the more candidates they can potentially attract. The three most sought after universities are referred to by the diminutive “SKY”, which stands for “Seoul National University”, “Korea University”, and “Yonsei University”. Getting into one of these universities gives access to a whole network of connections close to economic and political powers. It is a factor of social promotion and mobility, of highly-remunerated job opportunities and the key to ‘good’ marriages. Middle class families prepare their children a long time in advance (as early as kindergarten), through expensive extra-curricular lessons provided by private tutoring establishments. Known as “hagwons” these establishments (all 100,000 of them) generate approximately 2% of the country’s GDP and attract more than three out of four students. Indeed, it ha become commonplace nowadays for families to sacrifice everything in order to finance the studies of their children, spending sometimes up to a thousand euros every month per child until the end of high school, with the hope of obtaining the best possible ranking in the “Suneung”. Moreover, university fees constitute a significant expense, even in the case of non-private universities.

The Montreal Centre for International Studies (CERIUM in French) reports that each year, on the day of this exam, the whole country holds its breath: most offices and administrations close or open later in order not to interfere with the arrival at exam centers, late students are brought by the police and the entire airspace is closed off during the oral comprehension test.

Traditionally, Confucian culture is centered on education, as it is the case in China and Japan. In South Korea, the effective business of education coupled with parents’ obsession over their children’s success – leading them to consider the exorbitant amounts spent in education as rational investments for their future economic situation – amount to children being under an enormous pressure (they study on average 50 hours per week which is 16 times more than the average in OECD countries). The substantial decrease in birth rate – the fertility rate, 1.15 children per woman, remains one of the weakest in the OECD – is directly linked to this situation. It has become inconceivable to think of making children without being capable of undertaking the “socially necessary” expenses “good parents” have to make. The demographic consequences are very real: South Korean society has been deeply transformed by the aging of its population and the inevitable immigration of foreign labor.

The demands of this super-technological consumerist society have led to abuses, especially in regards to the younger generation, robbed of its youth and left psychologically strained. The extremely high suicide rate of this category (ahead of Japan’s) attests to this, alongside the consequential spread of new protest movements.

There are a number of private universities that, for the most part, don’t even guarantee the desired social status and produce generations of unemployed frustrated graduates – marginalized and socially discredited.

To sum things up, succeeding at the “Suneung” is succeeding at life!….and failing it, is hell…

Marie-Orange Rivé-Lasan and Eunsil Yim

Marie-Orange Rivé-Lasan is a historian and lecturer at Paris Diderot University (UPD)/UMR 8173 China, Korea, Japan (EHESS-CNRS-UPD) and Eunsil Yim is an anthropologist, UMR 8173 China, Korea, Japan (EHESS-CNRS-UPD)

(3.5 / 5 A societal drama, taking the shape of a bittersweet feel-good movie, which has the merit of putting the spotlight on the outcasts of Japanese society.)

(3.5 / 5 A societal drama, taking the shape of a bittersweet feel-good movie, which has the merit of putting the spotlight on the outcasts of Japanese society.)The director of NOBODY KNOWS, STILL WALKING, LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON, returns with this bittersweet drama displaying hints of comedy which won the Palme d’Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. The film owes its success to the noteworthy performances by Kore-eda’s treasured actor Lily Franky and Sakura Ando – revealed by Sono Sion in the cult classic LOVE EXPOSURE.

SHOPLIFTERS

(万引き家族, Manbiki kazoku)

A film by Hirokazu Kore-eda

With Lily Franky, Sakura Ando, Mayu Matsuoka

2018 – Japan – Drama – 121 min – 1.85:1 – 5.1 Sound – Audio: Japanese

| Screenplay: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (4.5 / 5) (4.5 / 5) |

Palme d’Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, Shoplifters – not necessarily Hirokazu Kore-eda’s most accomplished movie – has, if anything, the merit of having brought some attention to the marginalised and underprivileged of Japanese society.

The social reality of the country is rarely discussed, even by Japanese media, due to a decade-long preconception that Japan had resolved class struggles and conflicts by effectively eradicating the problem of poverty. The exceptional speed at which the archipelago recovered from the dire state of ruins in which it found itself after the Pacific war, becoming by 1968 the second global economic power, had led to, in less than a generation, an important restructuring of the social fabric. Because of the strong economic growth which resulted in a sudden rise of living standards as well as a significant expansion of the middle class, a vast majority of Japanese citizens considered themselves the beneficiaries of a nation-wide success, believed to be accessible to all. Someone is poor as a direct consequence of his merit, or rather lack-of. The suggestion that, in reality, the promoted economic model couldn’t actually prevent social inequalities from flourishing, was briefly treated by a faction of independent cinema in the 60s, but soon became taboo and was swiftly replaced by the seductive myth of “100 million inhabitants, all part of the middle class” [1]. The commercial flop and corresponding critical response met by Akira Kurosawa’s 1970 film Dodes’Kaden which depicted the living conditions of a slum, is symptomatic of the general state of mind of that period.

The proportion of people living under the poverty threshold (coined at half of the median income of the total population) has been kept under the covers, insofar as the Japanese state has never released official statistics capable of measuring its extent. The poverty rate was only established in 2002 as part of the Human Development Report conducted by the UN. The study determined that the percentage of the population living under the poverty threshold was of 11.2%. In 2005, an OECD report updated this number – placing Japan in fifth position of the member countries with the highest poverty rates, behind Mexico, Turkey, the United States and Ireland. Heavily covered, the word was out: Japan’s reality was no longer in line with its advertised image of prevailing and indiscriminate prosperity.

The situation affects the younger generation, constrained to accumulate small jobs without much prospects of promotion, but also concerns increasingly isolated women and older people. Employment insecurity has led to a plunge in revenues for many households, many of which having subsequently disintegrated. Although it had played a crucial role in the affirmation of the Japanese society, the family unit – once able to unite three generations under a single roof – has started to falter following the repercussions of the economic crisis. Accordingly, the number of single-parent families, often involving single-mothers employed part-time, has continually escalated (from 6% in 1990 to 10.5% in 2015). The turn of the century saw the emergence of a now infamous issue, the aging of the baby-boomers (in 2013 the elderly made up 25% of the total population) and the adjacent problem of retirement pension funding. Despite an increase in expenses to solve this impasse, the proportion of elders living underneath the poverty rate, at 19%, is a record high amongst OECD countries.Since the 2008 global economic crisis, the Japanese economic growth stagnates around 1% and its poverty rate remains high: 16.1% of the population lived under the poverty rate in 2012 and decreased slightly to 15.7% in 2015 (in comparison, in 2016, France’s rate was at 8.3% and the United-States’ at 17.8%). The figures attest to a more alarming situation when it comes to single-parents families and children, their respective poverty rate soaring at 58.7% and 16.3, the highest of all OECD countries. From Nobody Knows, presented in the official competition of the 2004 Cannes Film Festival, which highlighted the issue of single-parent families through the lens of a news story, to Shoplifters which deals with poverty-stricken children and retirees, it is clear that some of Kore-eda’s main concerns correspond to the social degradation at play in his country.

Since the 2008 global economic crisis, the Japanese economic growth stagnates around 1% and its poverty rate remains high: 16.1% of the population lived under the poverty rate in 2012 and decreased slightly to 15.7% in 2015 (in comparison, in 2016, France’s rate was at 8.3% and the United-States’ at 17.8%). The figures attest to a more alarming situation when it comes to single-parents families and children, their respective poverty rate soaring at 58.7% and 16.3, the highest of all OECD countries. From Nobody Knows, presented in the official competition of the 2004 Cannes Film Festival, which highlighted the issue of single-parent families through the lens of a news story, to Shoplifters which deals with poverty-stricken children and retirees, it is clear that some of Kore-eda’s main concerns correspond to the social degradation at play in his country.

Visibility problems

In a study dedicated to the issue of urban poverty in Japan, after two years of field research, French sociologist Mélanie Hours has emitted the hypothesis that “what is really problematic (in the Japanese archipelago) is not so much the existence of poverty, but (more pressingly) its visibility” [2]. It is in this context that the cited films have a particular worth and resonance. Constructing her thesis around three main arguments, the author has concluded that “the absence of a national poverty rate, the small amount of welfare beneficiaries (only 1.6% of the total population) and common refraining from even employing the term “poverty”, perpetuate the myth of its absence and reveal a deeper issue of denial”. If the myth of a society without poor people is sustained despite the evidence, it is due to the fact that, for a majority of Japanese people, poverty is relegated to the background. It is indeed much easier to remain convinced of the inexistence of misery if it is out of the “ordinary” citizen’s field of view.

Beyond the question of “denial” and of the state and medias’ responsibility, we could add to Hours’ arguments, the fact that a Tokyo inhabitant, in his daily life, doesn’t have many possibilities of encountering, if only visually, the less fortunate. Their non-visibility is to be understood in the most literal sense. The reason lies in the very arrangement of Japanese metropolises. Poorer areas do exist to varying degrees of extent and dilapidation and are, in a city like Tokyo, scattered throughout the enormous urban fabric that represents the Japanese capital. While the capital’s old topography showed a clear distinction between the more affluent areas, often situated in the north-west axis, and working-class neighborhoods situated on the opposite side, its widespread development in the aftermath of the war, has significantly modified this configuration. Now based on a more scattered model of districts, whose main commercial activities are centered around train stations, Tokyo comprises a network of small urban zones on the edge of which are situated the more modest dwellings, consequently far from big transportation passages. Passing by some of the poorer areas when leaving town constitutes a casual part of Europeans’ lives – something relatively unheard of in most Japanese agglomerations.

A second factor which fosters this non-visibility in Japanese cities is the scarcity, if not absence, of beggars and homeless people in animated and touristy areas. It isn’t rare for foreigners, after a trip to Japan, to assume that there are simply no beggars and homeless people. It is important to note that Japan isn’t a traditionally Christian country and that begging, while it isn’t completely forbidden, is regarded as a disgraceful practice. It is therefore useless for homeless people to even go in some areas.

Japanese society rests upon moral values that descend from neo-Confucianism, which, during the Edo era (1603-1868), was elevated to the rank of official ideology. Although the successive constitutions which organized Japan have put a term to the pre-eminence of this ideology, social interactions are still, to this day, in large part influenced by some of its precepts. Begging is considered dishonorable, because in a Confucian-imprinted culture, being a weight for others is shameful.

We should underline that Confucius, in his time, made the distinction between “the superior man”, involved in state affairs and the nation’s future, who’s behavior modeled those of the ancient Sages’, and the “small person”, incapable of controlling and shaping his personal desires. If ever a man were to fall in disarray, in order to preserve the greater good, he would be summoned to take a step back and “live in poverty without any resentment” [3]. Confucius developed this thought in a famous precept, according to which “the archer has a common point with the sage: whenever his arrow fails to reach the target, he must find the causes within himself (rather than accuse anyone else)” [4], implying that the “superior man demands everything from himself (whereas) the small person demands everything of others.” [5].

This trait helps us better understand the reasons for which poverty in Japan is traditionally associated with the notion of worth. A poor individual is the sole responsible of his situation, and shouldn’t rely on other to help him solve his own problems. Indeed Hours in her study shows that the residents of Sanya, one of the poorest districts in Tokyo, while aware of their position of increased weakness facing the crisis, but can’t help but feel responsible for their situation – which evidently constitutes a hindrance to their very desire to better it.

This cultural characteristic rooted in Japanese society doesn’t only explain the absence of begging, but also the fact that a large number of people in need are reluctant to seek out any help from public services. In both cases, the mere thought of becoming a burden to society represents a moral obstacle, difficult to overcome. The situation is comparable, in a way, to the experiences of Japanese hostages in Iraq and Syria. Independent journalists gone of their own free will, they had provoked the contempt of a large portion of society which considered that the State had no obligation to help them get repatriated. The feeling of shame is increased by further societal disdain.

« Oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi » (« Dehors les démons ! Dedans le bonheur ! »)

Rather than benefiting from public assistance, a large majority of the more unfortunate choose to have a professional activity, however arduous and not rewarding. The low unemployment rate (2.8% of the total population in 2017) is to be compared with the fact that 37% of employees have a precarious status (versus 13% in France). Amongst the different type of contracts, let us mention the one of daily worker – like the father in Shoplifters – “referred to as ‘job of the 3Ks’ referencing the words kitsui, annoying, kitanai, dirty, and kiken, dangerous” (6). If such activities make day-rentals at attainable costs possible, the line is thin between such accommodations and being homeless. Indeed a non-renewal of contract, on the table every single day, leads inevitably to the streets. Obviously, this type of employment doesn’t offer any social security net nor the possibility to contribute towards a retirement plan.

Again according to Hours, a majority of the homeless have professional activities, attached to small salaries, like the collection of cans and journal, or even a regular job but which doesn’t permit decent housing. Many homeless people live in communities inside small camping sites. Located in remote areas, sometimes bordering rivers, they are generally hidden from the public eye. Some homeless shelters might be located in public parks, recognizable by the blue covers on top of most of them, but always distanced from the principal passages.

In these areas, community life rather than individual effort is favored first because it facilitates finding an activity but also because of the value of collective effort and support. Although voluntary associations can provide relief at least with regards to the most elementary means of subsistence (medication, food,….) as shown by Kiyoshi Kurosawa in his film Tokyo Sonata (2008), where he films the distribution of free meals, it is still the case, according to Hours, that assistance to the poorest is often organized by the poorest themselves. Just like the characters in Shoplifters who seek to recompose a social group, however small, through which they could regain an identity and which could offer them the opportunity to take-on a set of responsibilities towards a group of people. Such a system, once again, can strongly limit the will to go back to a “normal”, “standard” life.

The problem was further accentuated in the 2000s particularly in Tokyo where the authorities in power proceeded to dismantling homeless shelters, in the name of cleanliness or urban-planning projects, expulsing then relegating their populations to the outskirts of the city. Not only did this worsen the problem of non-visibility, this exclusory political action amounted to widening the divide between the spaces that claim to have eradicated poverty and others, unable to boast the same advantages.

As it is lived in Japan, poverty goes beyond financial and material considerations: being poor is not only defined by a lack of possessions but also as lack of utility to and interest from society as a whole. If the myth of a society rid of its poor can be perpetuated to this day, it is probably due to the fact that the poorest are no longer considered as being an integral, functioning part of society.

The most deprived, in other words, aren’t only relegated to the bottom of the social ladder, but simply excluded of the communal space. The characters of Kore-eda’s film reside in a decrepit house, covered in vegetation, and encircled by tall buildings which gives an eloquent image of this phenomenon of exclusion. In a way, the great poverty found in Japan, reproduces the ancient model of murahachibu, the one which is banished from his village for moral reasons, without any hope of returning. Unlike the excommunicated in ancient catholic countries, who, thanks to the doctrine of repentance, can be hopeful as to a possible reintegration, escaping eternal damnation. The Japanese form of exclusion, makes the lived experience of the banned person, a living hell, dispossessed of what makes him human.

In the steps of Kore-eda, cinema but also literature (for example the novel Tokyo Ueno Station, published in 2014 by Yu Miri which deals with the issue of homelessness), can contribute to a better appreciation of these problems, the main objective for anyone preoccupied by the subject consisting first and foremost in giving back some dignity and consideration to those who have been deprived of any attention at all.

Nicolas Debarle

A specialist of Japanese cinema, Nicolas Debarle is the author of many articles and festival reports published through internet (French online magazines Il était une fois le cinéma, EastAsia). He teaches French in Tokyo where he has been living since 2012.

[1] « Le taux de pauvreté en augmentation au Japon », 2014, https://www.nippon.com/fr/features/h00072/

[2] Mélanie Hours, « La pauvreté urbaine au Japon », p. 9, 2007, https://journals.openedition.org/transcontinentales/747

[3] Entretiens de Confucius, XIV, 11, p. 112, traduction d’Anne Cheng, Ed. du Seuil, 1981

[4] L’invariable milieu dans Les Quatre Livres, p. 34, édition électronique en ligne, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5421352k

[5] Entretiens de Confucius, XV, 20, p. 124

[6] Mélanie Hours, 2007, p. 5

Qiao is in love with Bin, a local mobster. During a fight between rival gangs, she fires a gun to protect him. Qiao gets five years in prison for this act of loyalty. Upon her release, she goes looking for Bin to pick up where they left off.

ASH IS PUREST WHITE is Jia Zhang-ke’s third film to be presented in the official competition of the Cannes Film Festival.

ASH IS PUREST WHITE

(江湖儿女, pinyin: jiānghú érnǚ)

A film by Jia Zhang-ke With Zhao Tao, Liao Fan, Xu Zheng

With Zhao Tao, Liao Fan, Xu Zheng

2018 – China – Drama – 136 min – 1.85: 1 – 5.1 sound – Mandarin

| Screenplay: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (4.0 / 5) (4.0 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (4.0 / 5) (4.0 / 5) |

Up until the 80s, Chinese cinema was an “eminent stranger” to the West… Associated for a long time to a single genre – the one of martial arts, actually only really popular in Hong Kong – it revealed its true colours at the memorable 1985 Locarno Film Festival. Chinese cinema was at the time represented by two great talents: Hou Hsiao-hsien from Taiwan and Chen Kaige from mainland China. This revelation contributed to dissipate the confusion surrounding this region: it was first of all brought to our attention that there existed three different Chinese cinemas corresponding to three very unequal zones and that Chen Kaige was the figurehead of a fifth generation of directors, implying the existence of a whole lineage of directors whose efforts had helped produce the displayed level of quality.

In Chinese cinema, different generations indicate to different stages, or even styles, of its history. The first occurs between 1913 and 1932, encompassing the silent period; the second, from 1932 to 1949, represents the establishment of sound and the golden age of realist cinema, epitomized by the masterpieces The Goddess (1934) by Wu Yonggang and Street Angel (1937) by Yuan Muzhi; the third develops between 1950 and 1966 and is the expression of social realism (Zhang Ga, the Soldier Boy (1963) by Cui Wei); the fourth period unfolds after the tragic decade of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), with films such as Troubled Laughter (1979) by Yang Yanjing, paving the way for the fifth period, which definitely launched Chinese cinema onto the international stage. Young directors ranging from Chen Kaige, Zhang Yimou, to Tian Zhuangzhuang, after leaving the Beijing Institute of Cinema in 1982, undertook the difficult task of remodelling Chinese cinema, meaning it had to be stripped of its political and ideological undertone. They turned their focus to a new type of individual, capable of expressing his feelings and sorrow on screen, after years of ideological extremism. The films became increasingly intimate, leaving the socialist heroes behind… After kicking-off in 1984 with Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth, the new Chinese cinema started collecting awards from international festivals: Golden Bear for Red Sorghum by Zhang Yimou at the 1988 Berlin Film Festival; Best film and best female actress for The Blue Kite by Tian Zhuangzhuang at the 1993 Tokyo Film Festival.

The beginning of the 90s marked a turning point in Chinese cinema. The directors started taking interest in the individual’s existential journey and his hardship when navigating the constantly evolving society. They progressively moved away from rural landscapes and the allusive and metaphorical forms used by their predecessors to adopt a more realist approach. Just like the fifth generation, it is once again in the midst of a dramatic event that the new generation defined itself: the tragic repression of students protesting on Tiananmen Square in June 1989. The group was then faced with a dilemma: no official studio was willing to open their doors to students, all seen as part of a subversive force. What next? Stay idle and wait for years in the hope of being summoned for a film or look for other options? Courageously, the new graduates opted for the second option and decided to venture off the beaten track. Because access to institutional circuits of film production and diffusion was, and still is, dependent on the Cinema Bureau’s endorsement, the young directors decided to create an alternative space to work in. Instantly, their cinema became part of a greater nonconformist movement moving outside of societal bounds. This marked the beginning of an independent production, the survival of which remains a factor of international support. A few years away from the turn of the century, China displayed a fragmented cinematographic scene, separated in two separate factions.

The films of the new generation, known as the “Sixth generation”, broadcast a profoundly urban awareness. They testify to the silver linings of the economic miracle -misery, unemployment and disarray facing the brutality of socio-cultural transformations. The now internationally famous Wang Xiaoshuai (Beijing Bicycle) and Lou Ye (Suzhou River) are part of this generation.

Their cinematographic style, unlike the previous generation, is inspired by documentaries, which have developed a proper artistic expression of their own. The digital camera, a tremendous tool, has played a huge role in this evolution. Potentially very discreet, easy to handle and comparatively cheap, this technological advance has opened up new prospects for audiovisual creation in which the younger generation can flourish, motivated by an unprecedented enthusiasm. This camera gives them the possibility to film big cities as well as more remote areas where more disadvantaged groups live. Today, as Chinese cinema enters globalization, many figureheads of the more auteur trend of the 80s and 90s are turning towards commercial cinema: in 2006 Zhang Yimou inaugurates, with Curse of the Golden Flower (a historical epic recalling China’s imperial past), the trend of super productions likely to become future box-office hits, in China but internationally as well. This makes it easier to surpass censorship and benefit from the financial help of producers willing to invest in a project whose goal is to be massively distributed.

Other directors, however, continue to defend a certain vision of cinema, distinct from these super productions. It is through this independent agenda that they are able to define and cultivate a personal and original relation to the world. And, of course, to cinema.

Luisa Prudentino

Specialist of Chinese cinema, Luisa Prudentino teaches the history of Chinese cinema at INALCO since 2008 and leads various seminars, symposia and conferences in France, Italy and China. She is the author of “Le Regard des Ombres” (The Eye of Shadows) (Bleu de Chine, 2003) now a reference in the subject matter.

In the late 70s, a gang of militias under the control of the military, terrorizes a remote village in the Philippines. The poet/teacher/activist, Hugo Haniway, decides to find out the truth about the disappearance of his wife. A love story set in the darkest period of Philippine history, the Marcos Dictatorship. Based on real events and real characters.

‘Season of the Devil’ premiered at Berlin International Film Festival this year.

SEASON OF THE DEVIL

A film by Lav Diaz

With Piolo Pascual, Shaina Magdayao, Pinky Amador, Bituin Escalante

2018 – Philippines – Drama – 1.50 – 234 min – Audio: Tagalog

In French theaters on July 25, 2018

Join the official Facebook page: #ResistTheDevil

Lav (Lavrente Indico) Diaz, born December 30, 1958 in Cotabato, Mindanao, is a Filipino filmmaker that is also a screenwriter, a producer, an editor, a cinematographer, a poet, a composer, a production designer and an actor. One of the most notable characteristics about Lav Diaz’s films is their length (some are more than 11 hours long). His films often address political and social issues and more specificially the struggles of his people throughout History and that is what earned him the visibility and admiration from the best international film festivals.

Lav Diaz made 12 films since 1998 and received numerous international awards, including Locarno Golden Leopard (‘From What is Before’ in 2014), Berlin Silver Bear (‘A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery’ in 2016), Venice Golden Lion (‘The Woman Who Left’ in 2016).

The French public only became familiar with Lav Diaz’s cinema in 2013 when ‘Norte, the End of History’ was introduced at Cannes Film Festival at Un Certain Regard. A full retrospective followed at Jeu de Paume in Paris in 2016 as well as the release of ‘Death in the Land of Encantos’ and ‘The Woman Who Left’ in French theaters. With ‘Season of the Devil’, it’s the fourth time a Lav Diaz film is released in France.

How did the idea of a ‘rock opera’ occur to you?

I was at Harvard University in September 2016 for a residency program. Part of my project with that residency was to write a script for a gangster film called ‘When the Waves are Gone’. I also started writing a book about Filipino cinema called ‘A liberated cinema’. I started writing songs as well -the songs kept coming. We had a new president back home at that time (Rodrigo Duterte was elected in May 2016). And things drastically changed as I read the news about the country: the so called drug war became really bloody in terms of human rights abuses, specifically during the first months of Duterte’s tenure. So I started addressing the issue, again going back to the struggles of my people. And this fed the themes of the songs I was writing that kept haunting me. Then around November, I e-mailed my producer Bianca Balbuena and I requested from her we put aside the gangster film because my focus now was into doing some kind of an opera, a musical about what’s happening in the country. There was a sense of emergency. I told her we needed to do this so that we could at least do our part in addressing the issues of what was happening in the country. It was a question of responsibility as an artist. Bianca agreed and we focused ourselves right away. I told Hazel Orencio to start working on the casting as well. We decided to shoot the film in Malaysia. By mid-January, we already started the production in Malaysia. We completed the shooting in Malaysia around the first week of March 2017 and edited the film for about three months in Manila.

Would you say your art is dictated by a sense of emergency? Are your films responses to ongoing events like for ‘Death in the Land of Encantos’, a nine-hour film you started shooting only a few days after typhoon Reming hit the Bicol Region in November 2006 (even though it was first meant to be mere footage with a testimonial value)?

In the case of ‘Encantos’, the immediacy of what I saw became the inspiration of the film. I lived in that region for a year. I got there 5 days after the storm and everything was devastated.

I had no plan indeed. I just went there to shoot and maybe give the footage to the news bureaus. After a few days of shooting and recording, it was so heart-breaking, horrifying, harrowing, I watched the footage and thought maybe I should build a story around and it’d be better to do it that way, it can be a good memorial, some kind of a tribute, in homage to what the place used to be. I thought of characters I could focus on in the continuing narrative of what can be done. So I invited those three characters, Roder, Angeli Bayan, Perry Dizon…

So, yes, it’s a response. Not just a response, there is an urgency, a call: it’s a responsibility to do it, to engage in what’s happening, using the medium. As a filmmaker that’s all I can think of I can do. Maybe I can make a film about it, to raise some awareness, confrontation with the coming cataclysm.

The most immediate advocacy medium for me is cinema.

It’s almost the same process for ‘Season of the Devil’, except that the idea -though inspired by ongoing events- preceded the shooting.

Why did you shoot ‘Season of the Devil’ in Malaysia?

There were two reasons. 1) It was very risky to shoot the material in the Philippines -the police are everywhere, checking everybody. Shooting in the Philippines would have required police permits and they’d be watching. And they’d have sensed: ‘Oh, the film is about our guy…’. They’d have checked in on us all the time and we wouldn’t have been free. The other reason is we have two very popular actors, Piolo Pascual and Shaina Magdayao. It’s hard to shoot in the Philippines if you have those superstars: if fans found out, we wouldn’t have been free either! In Malaysia, nobody cared because they didn’t know us. And the village we shot in looked very much like what we were looking for.

How about the rock opera form?

Music as an art form came to me before cinema. In college, I joined several bands, I wrote songs and also poems. I was more specifically into rock music: three quarts four quarts. That kind of pattern, the verse and the refrain and then you go back. Writing songs is a very fluid activity for me. That’s probably why the songs of ‘Season of the Devil’ spontaneously came to me. When I decided to do the film though, I did not want anything close to the conventional musical as we know it (the Broadway or Hollywod way, with the movements, the dancers, the big bands, the accompaniment etc.). We did without those things, we did it a cappella and used the songs as dialogs. It wasn’t important to have really good singers: as long as they could actually sing, even in a very raw manner, as long as they could follow the beats and remember the melody, then it was fine. The real stake was more about the actors’ political perspectives or leanings. Since the film is about fascism and its rebirth in the Philippines, even though it’s set in 1979, we could obviously not run the risk to work with anybody pro-Duterte or pro-Marcos. We had to be very careful about that criterion.

Your films are known for their long takes and their long shots, not to mention the recurrent use of black and white. Can you come back again to that trademark of yours for the readers who might discover your films only now? Can you also explain how different ‘Season of the Devil’ is to that effect?

I grew up watching a lot of black and white films -my father used to take me to the movies every weekend and I watched up to eight films a week. All kinds of films: Hong Kong movies, western movies, Japanese films etc. -always in black and white! Cinema is in my head, in black and white. The world is so full of colors. If you see it in black and white, it’s a whole new universe, it’s another way of seeing the world. That alone is very important, the aesthetic sense that it’s our universe but it’s another universe. For me black and white is very mysterious and it makes us see things differently.

The pursuit of truth is the genesis of my long struggle with film praxis; the struggle to embrace a mise en scene that can approximate or just appropriate the discourse on truth; even on a theoretical level, as truth is relative, elusive; as a principle, mythologizing is the enemy, or, the more colloquial word, compromise; for practitioners of cinema, application remains the key to the struggle for the truth; the application of which I found on my use of the long take and the discipline of one-frame shot; even with my actors, the long take or one frame shot they’d realized to be a more useful/truthful framework in the delineation of characters they’re portraying because their flow is bothered by cut-to-cuts or full coverage shooting, which is the convention.

I don’t really think about length when I make films. I’m a slave to the process, following the characters and the story and where they lead. I immerse the actors first; I tell them about the scene, maintain conversations with them on set but do not instruct them. I trust the actors and I just follow them with the camera where they lead. Everything is very organic. It’s my method. As a matter of fact, my films are not long, they are free. I just keep shooting and shooting once there’s an idea. When I watch the footage later, if I think there’s still more to be done, I have to shoot it. Perhaps I think this way because, with regard to the history of my people, we don’t really have a concept of time, we just have a concept of space. Time is a very Western concept for us. The space in Asia is very archipelagic: we have the islands, we have everything, and we’re governed more by nature than time. In fact, we, Malays, are governed more by space and nature than conventional time.

For ‘Season of the Devil’, I adjusted to the rhythm, to how the characters performed the verses, the songs. The cutting of the film was dictated by the rhythm, the beat. I struggled with that. I did very long takes. But at the end of the day, once the singing stops, there’s a big lull and it feels awkward not to cut. I said: the long long takes won’t really work. There’s a long silence, they’re not doing anything, they couldn’t say anything more. There was no two ways about it.

The film alludes to a number of concepts, surrealist or folkloric references…

‘Season of the Devil’ is very conceptual indeed: there are a lot of mythological perspectives in the film, it’s an allegorical thing, I used symbols, animals, semiotics… I used folklore and paganism: the owl, the snake, the traitor, and I also used some Western culture mythological figures such as Narcissus to create the character of the head of the village, the two-face Janus guy. Likewise, Teniente is a composite of those fascist military leaders that existed during the Marcos years. Having a woman actor (Hazel Orencio) portraying a male persona was part of the concept. Teniente is a brutal macho lieutenant, the head of a military unit. All those people are based on real characters.

Generally speaking, your films are very conceptual –they use strong aesthetics, metaphors, symbols to address political issues and denounce abuses. They’re also in black and white and usually pretty long –this one is almost 4 hours long and it can go up to 10 hours… Aren’t you afraid you films may be perceived as elitist, meant for an elite audience only?

There’s a key thing to understand: you can educate people without compromising your work. Or should the films be less than two hours for instance? That’s a compromise! Art is not about complying with conventions and archetypes. At the same time, I am convinced cinema can change the way we see and perceive things. It’s the most powerful medium. I do have faith in cinema. It can change the world. I believe so. That’s why it’s important to propagate it. Festivals, film programmers, distributors, universities play a key role to that effect. We also have to find alternative ways to reach people the Socrates way. Go the plaza, to the markets and talk to people. We should bring uncompromising cinema to people by engaging them: we have to reach out to people and also tell them to do sacrifices as well -forget about popcorn, coke etc. [laugh]

In the case of ‘Season of the Devil’, cinemas are very limited indeed. There should be other venues or we should be mobile, go to campuses, reach out to people. You have to find places, to create venues and the dialogue between art and people. Netflix is a venue too, why not? Just as long as the film is not compromised. Streaming is part of cinema now.

You have to find places, to create venues and the dialogue between art and people. Netflix is a venue too, why not? Just as long as the film is not compromised. Streaming is part of cinema now.

You make films about the dysfunctional politics of your country. Have you ever met any kind of pressure or resistance in doing so?

Not until now because no matter the international recognition gained by the festival awards, I’m still a curiosity more than a reality in the Philippines, i.e. an artist among intellectuals, the artists’ community, the academia… But among the masses, I’m still an obscurity, a curiosity. They maybe know the name or the face but they don’t know the work although I’ve been questioning the policies implemented by the different dictators and corrupt regimes of our country for a while. The safety comes from not being seen by the masses. Maybe one day… then will come the danger.

Masses don’t like uncertainty… Is it the reason why we witness the rise of populism in so many countries?

The problem is ignorance, that’s the reason why there are rising populist leaders everywhere. But there’s also a lack of actual engagement among the people that are aware of what’s happening -the intellectuals, the elites, the so called experts. Associating with each other only has cut them off from reality, leaving the masses by themselves. Look at the greatest institutions in the US for instance (Harvard, Stanford, Columbia) but what do they have? Trump. So we need to engage more: do not confine education to campuses. We need to reach out to the masses, break the walls and barriers while standing up for our convictions.

You once said the Philippines is the less Asian of Asian countries.

It’s a question of perception that is connected to religion. In the Philippines, 90% of the population is catholic, catholicism and christianism being Western concepts that date back from the colonial times -the Philippines was first a Spanish colony then an American colony. A lot of people perceive us as non-Asian for those reasons, because of the American influence. It’s a weird perspective but it’s real.

The fact is Filippino people are actually Malays. And we’re not less Asian than Malays just because we’re catholic. We know we are Malays but we don’t understand why we are Malays. It’s a big problem with our psyche. Again we need to engage the past, to confront the past. The thing we need to understand is we have histories before they created our history based on their impositions. Our history now is based on their histories. Whose history are we dealing with? The written history that’s imposed by the Western media and colonial heritage with their ‘national heroes’? We need to have our own version of it, based on the truth that we had before they created our truth.

Likewise, we have to correct what ‘Asia’ is about. It is true though that the notion of ‘Asia’ is just a discourse, a perception. Who is Asian? Even the Soviet block considers itself as Asian. The meaning of the word Asia is just semantic indeed.

Asia is both an issue and a non-issue. What’s most important is the discourse, how you explain the ‘label’. For instance ‘Asian film festivals’ is another venue for discourse and how to correct things about what Asia is. Asia is more a geopolitical than cultural concept.

Asia Etcetera is born completely out of the blue! There was no specific plan at first. There was just an interview with Filipino filmmaker Lav Diaz on the occasion of the world premiere of ‘Season of the Devil’ at Berlin International Film Festival followed by the release of the film in French theaters. The volunteer interview was planned to be published in a new French lifestyle magazine dedicated to Asian cultures. It was published early this month but the text, though granted two inside pages, was nevertheless significantly edited without the author’s consent so that frustration led to positive energy and the idea of some kind of online magazine dedicated to Asian cinema and cultures -uncensored, unrestricted and out of the box. To resist is to create indeed!

‘Some kind’ because it won’t be a traditional magazine with reviews and extensive coverage of must-sees. Actually, it won’t even necessarily be about cinema… Maybe it won’t even be about ‘Asia’ the way we see it. What is Asia indeed? That’s a key question this place will try to explore all way long, in French and in English (and we hope you’ll indulge our non-native English).

In short, in ‘Asia Etcetera’, the most important word is ‘Et cetera’, that is ‘what is missing’. Let’s find out together and try to gather the pieces! 🙂

In the meantime, please bear with the work-in-progress layout and content of this website (and feel free to let us know what you think).