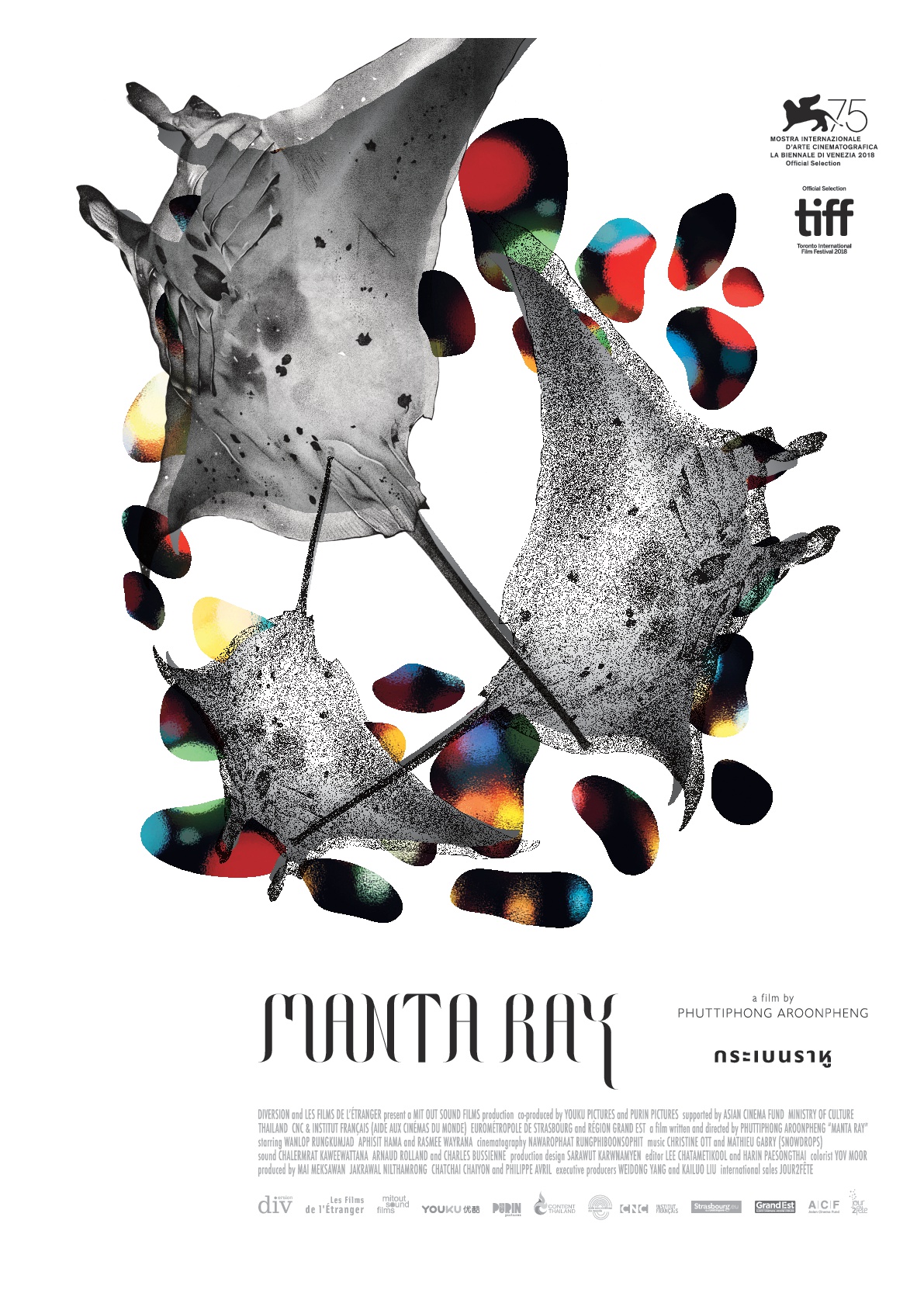

Mai Meksawan worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival since 2004, and was its programmer until the festival’s final edition in 2009. He also programmed and co-organized several other festivals in Thailand. In 2007 he co-founded, with Pimpaka Towira and Ruengsang Sripaoraya, production and distribution company Extra Virgin, where its most successful title, Agrarian Utopia (dir. Uruphong Raksasad) screened in more than 100 film festivals worldwide and received 11 international awards. He founded production company Diversion in 2014. His most recent films as a producer include Manta Ray (dir. Phuttiphong Aroonpheng), winner of Orizzonti Award for Best Film at 2018 Venice Film Festival, Come Here (dir. Anocha Suwichakornpong), which premiered at Berlin Film Festival this year, and Anatomy of Time (dir. Jakrawal Nilthamrong), which is premiering at Venice Film Festival in the Orizzonti section right now.

What is your journey to film production? How did you end up becoming a film producer? What is your background?

I started my career as a festival organizer, working at the Bangkok International Film Festival which during most of the 2000s was Thailand’s main international film festival.

I studied architecture in university but have finally never practiced it – interestingly, similar to Apichatpong Weerasethakul as well. And I then happened to apply for a position at the Bangkok International Film Festival, first in the publicity department, and ended up there through the years. I was one of the programmers there during the festival’s latter years, until the government eventually stopped the funding and the festival was put to an end. During that time I got to know a lot of new up-and-coming filmmakers, the films of many of them we showed at the festival too and whom I ended up working with to help develop their projects. So as things progressed, I finally became their producer too. To be honest I can say that I did not set out to be a producer in the very beginning. It gradually happened in a natural and spontaneous way.

You produced Phuttiphong Aroonpheng’s Manta Ray. How did you meet him? What made you want to produce Manta Ray?

It was through another filmmaker I work with, Jakrawal Nilthamrong. I first met Jakrawal in 2008 or so when we started working together to develop his debut feature film project. He introduced me to Phuttiphong, who was his long-time friend as well as a veteran cameraman. Phuttiphong is the director of photography of Jakrawal’s short films too – as well as of his first narrative feature film Vanishing Point. During that time, we heard that Phuttiphong was also developing his own feature film project, titled Departure Day, as a director and so we decided to get on board. The project eventually became Manta Ray.

It was an interesting development. For a lot of other filmmakers I work with, they usually start off doing short films before evolving into feature films. The usual route for independent filmmakers in our region is spending their early years in their career making short films and sending them to festivals in order to build up their profile, which will help them land bigger fundings in order to make a feature film that will become their big breakout. But Phuttiphong took another path because he had an extensive experience in production, working as a cameraman and production designer for both independent and mainstream films. He did actually not make a lot of short films. He just had a very clear and focused idea of what he wanted to achieve in his debut feature film straight from the beginning – with a level of self-confidence that not a lot of first-time filmmakers can have.

What was the most difficult thing about producing Manta Ray? What was the budget of the film?

It was a bit over 400,000 Euros, which is quite high for a Thai independent film, especially for a first feature film. We were lucky to finally manage to get funding from China and France – respectively through Youku Pictures, which usually works with more commercial films, and through CNC’s Aide aux Cinémas du Monde (World Cinema Fund) and Strasbourg’s region fund.

The process was quite long and at times it felt quite uncertain how everything would eventually turn out. The long waiting period was perhaps the main challenge because Phuttiphong started the first draft of the script in 2009 and we ended up finishing the film in 2018. During that period though he actually also got married and started a family. There were also a couple of years in between when the project was put on hold because Phuttiphong was busy as a DoP for other films so we only officially resumed the project in 2016. The film ended up very different from the original script because in the beginning, when it was still Departure Day, Phuttiphong conceived it as a diptych – with a twin storyline where the first half of the film revolves around one set of characters in one location and the second half entirely with another set of characters and location altogether. And the two halves of the story are only interconnected in a loose and spiritual way. But later on, Phuttiphong decided to lift the first part of the story and turn it into a short film titled Ferris Wheel, which he completed in 2016. The short film was very well received and played a crucial role for us to get started and finally make the feature film, which is the second half of the story of the original script – about the fisherman who rescues a mysterious stranger, who turns out to be a Rohingya. It was quite a gamble but paid off very well. I think one benefit of the film taking a very long time to make is that, by the time we landed enough funding to actually get to start shooting, the project had been with Phuttiphong for so long that he already had a very clear picture in his head of what he wanted to do for each scene in the film. So when the time came for the actual shoot it went very smoothly.

Was the film released in Thailand? How did the audience react to it? Did the international audience react differently?

Manta Ray was released in Thailand in July 2019 – about ten months after the world premiere in Venice. By the time of the local release, it had extensively travelled in festivals and received several awards that helped a lot create buzz for the local press and audience. Given its specific form, the film mainly attracted local cinephiles, so we had a small but dedicated audience.

Regarding the difference between how local and international audiences perceived the film: the local audience tends to focus more on the cinematic style rather than the political context – from what we’ve seen. The international audience also tends to compare the film to the works of other Thai filmmakers they are familiar with, which I guess we cannot do anything about, whereas for the Thai audience, it’s almost the other way round since a lot of people here noticed that the film feels quite different from most Thai films.

What is it in general that makes you produce films? How do you choose your projects? Do you have a specific editorial line?

So far I mostly work with people I have a close relationship with or have known very well for a long time. Making films is a very long commitment and requires a lot of perseverance, so you really need to believe in it and in the people making it –a good relationship is crucial. Given my personal taste, I have really only worked on auteur-driven arthouse films. They are the kind of projects I like and make me want to get involved. Back when I organized film festivals I enjoyed both the curatorial aspect – the work as a programmer – and the logistics pertaining to managing budget, operations and people, which is pretty similar to producing films in a way. But the festival scene in Thailand is very troubled and when you do a festival here, it is the people who finance it who have the final say on everything. So after a while, I realized that it was never going to be something of my own. At the end of the day, it is always going to be somebody else’s festival you work for. And so I became more interested in producing because it allowed me to achieve something that I could truly call my own.

How do you finance an independent Thai movie as a producer?

In every way we can! Mostly through grants I suppose: a lot of Thai independent filmmakers who received recognition overseas rely a lot on supports through international – mostly European – subsidies like the Hubert Bals Fund, World Cinema Fund, CNC Aide aux cinémas du monde etc. We also used to have a local subsidy through the Thai Ministry of Culture’s annual film grant, which helped support a lot of Thai films that went on to have successful international festivals career over the past ten years. Unfortunately, the program has been suspended a few years ago. So we have to keep looking for new financing sources. Private equity financing is a big challenge because it is next to impossible for independent films to recoup investments (although that can be true for commercial films too). An overwhelming majority of local films released each year in Thailand lose money and only a small fraction break even or make a profit because the production and distribution costs are always very high while the distribution revenues are getting smaller year after year. It is an extremely risky business. I once had a conversation with a producer from a very big commercial studio, who said that we independent producers hold an enviable position in a way, because we are completely free from the commercial demands of the marketplace and can afford to produce the kind of films we want to do without having to worry that it will not break even and generate enough profit to recoup the financiers’ investments because that is never going to happen in the first place! Commercial producers need a commercial success for each of their films, which implies a severe limitation of what they can say or portray in their films because their career and whether they’ll be able to produce the next film are at stake. Independent producers do not have that kind of pressure because once a film is finished, we proceed to work on the next one right away no matter if the previous film is a box office success or not. As a result, independent films have much more freedom to tackle a much diverse range of topics too. I had not really thought about it this way before and it is quite an eye-opening statement. It is not our intention of course to only make films for festivals and critical recognition without generating enough commercial income for our financiers because that won’t certainly be a viable business model in the long run but at the same time it is important that everyone is realistic and has the same expectation of what will be the place of the film, once it is finished, in the marketplace – what level of commercial results it could generate and what kind of exposure it will get. We always need to make sure we work with partners, who share this same understanding, which is of course never easy and limits our options a lot. But we have to keep looking.

What are your upcoming production projects?

We completed Anocha Suwichakornpong’s new film, Come Here, which premiered in Berlin earlier this year. It is her official third film following Mundane History and By The Time It Gets Dark, and it is generating good interests in the festival circuit. We’re also very proud to present Jakrawal Nilthamrong’s Anatomy of Time at Venice Film Festival. It is our biggest and most ambitious project so far, and also our first multi-territories co-production too – with co-producers from France, The Netherlands and Singapore. Jakrawal’s background is in visual arts and his works are usually very experimental and non-narrative with major influence from Buddhism. But for this project it is comparatively more narrative than his other works and we are very excited about it. Another one is Uruphong Raksasad’s Worship, which is a mix of documentary and fiction. Uruphong usually likes to explore the boundary between reality and fiction and his works always revolve around the lives and hardships of villagers in Thai countryside with strikingly beautiful cinematography that hides a dark hinge of melancholy. He is also now getting more political – which is quite natural given the way the Thai political situation is heading over the past year, where a lot of people are getting much angrier and outspoken – and the film also reflects this collective sentiment but in a more subtle way. We are also developing a new feature project by a first-time director Patiparn Boontarig. We have been working with him for a very long time as he is the First Assistant Director of Phuttiphong’s and Jakrawal’s films. The title is Solids by the Seashore and revolves around an intimate relationship between two young women in the south of Thailand – a predominantly Muslim region that is very culturally different from the rest of Thailand, which is long known as a Buddhist country. The south is also famous for tourism with its long stretches of coastline but has been suffering from worrying environmental damage over the years with the sea erosion. The local government has built a series of concrete seawalls to stop the erosion, which permanently damaged the beaches and ended up causing more erosion in different directions. The film also reflects on this issue and speaks about human’s ultimate failure at fighting nature and repeatedly trying to control the world they are living in. Lastly, we are working further on Phuttiphong’s new film Morrison. It is a more ambitious project and speaks about a subject that is totally different from his previous work – it’s about the collective memory of Vietnam war in Thai society and rock & roll music. But it retains Phuttiphong’s signature style of filmmaking with the similar atmospheric feel of Manta Ray but in a different direction.

How many independent/arthouse films are produced every year? How many are theatrically released in Thailand (in normal times)?

The independent scene here is active but I’m not fully sure about the exact number. Maybe something like 5-10 new films each year. Most of the independent films are actually released in cinemas here because most of the time the filmmakers self-release their films and directly talk to cinemas. Theatrical remains the principal way for Thai independent films to be seen by the local audience since there is virtually no DVD market anymore and arthouse films are usually not available on streaming. I guess one benefit of Thailand is that local cinemas are very open to release independent films so filmmakers can deal directly with exhibitors without the need of a distributor. But the catch is that the release can end up to be extremely limited: most independent movies would only get released on 2-3 screens – with only 1 screening a day and up to 2 screenings during weekends. So it is very limited. And cinemas can be very quick to remove the titles that do not perform well commercially within the first few days of release. So the films may be shown in cinemas for only 2 weeks maximum or even less than that. At the end of the day, they can be gone very quickly.

There are about 50 films (all genres and budgets) released per year, meaning one new local film released each week.

Since COVID, there has not been a lot of new independent films released in cinemas though.

How many movie theatres are there in Thailand?

There are two rival chains of multiplexes that dominate the market. Together they account for about 1,000 screens – one chain holding 60% and the other 40%. These chains do screen arthouse films too but in a very limited format as described above.

As far as arthouse cinemas are concerned, there are only two of them – all in Bangkok. And one of them actually closed last year due to the impact of COVID-19. So now we only have one 3-screen arthouse cinema left, so it is vastly underserved for a big city like Bangkok. Technically there is also another independent cinema in town although they do not screen DCPs. It also closed down this year due to the pandemic again but it has recently been taken over by a local independent distribution company that will keep the venue running and continue the screening program, which is good news.

That main arthouse cinema is “House Cinema”, which is Thailand’s first cinema dedicated to arthouse films. It is owned by Sahamongkolfilm, which is the country’s biggest distributor. They started to release arthouse films in the late 1990s because at the time they bought a lot of films in bundles from sales agents and needed to have an outlet to release them and eventually opened their own cinema. The other arthouse cinema was the Apex cinema chain, which operated the country’s last surviving standalone cinemas – they had three cinemas in the city center (Siam, Lido and Scala). After the emergence of shopping mall multiplexes, Apex switched their programming to focus on independent films, which became very popular. But it is very difficult to operate a standalone cinema in addition to a number of other factors too: the Siam was burned down during the violent crackdown by the military during the red shirt demonstration in 2010. The Lido closed down in 2018 when its landlord decided not to renew the lease and then the final nail in the coffin took place last year when the Scala had to close down because of the economic impact of COVID-19.

There was also the Bangkok Screening Room, which had been in business since 2016. It was also an independent cinema. It did not screen DCP though. It was affected by COVID-19 too and closed down at the end of March 2021. But fortunately, it is taken over by a local distribution company, Documentary Club, which will keep the cinema running.

There is no arthouse cinema in other cities so far. There are certainly growing arthouse audiences in many places but the market remains limited and it is obviously very expensive to operate a cinema. In cities like Chiang Mai, Khon Karen or Hadyai, where there are active university students communities, there are many audiences who are curious about independent films but the films would only screen in non-cinema venues instead such as local art galleries, bookshops or cafes. The screening quality is not high but it’s become the only way for these films to be seen there.

Streaming has changed a lot in terms of audience habits. Nowadays – and even before COVID-19 –, cinema attendance has dropped and the audience is actually becoming more accustomed to watching content online rather than on the big screen. It’s a development that is especially challenging for us given what we do.

Are there many film festivals in Thailand? What kind of audience do they address?

Actually, there is practically none nowadays. Back when I worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival, we had two international film festivals showing arthouse films from Cannes, Venice and Berlin, which attracted a significant local audience (film lovers, students, young professionals, international communities etc.). And there was also a number of smaller thematic festivals through the year – about 1 or 2 every month – so the scene was quite active. But over the years, it has become harder and harder for festival organizers to keep afloat. A lot of festivals, including the one I worked with, had to end at some point. It’s an unfortunate reality.

Why aren’t there any film festivals and film grants in Thailand anymore?

It is a complicated issue and we can have a very long discussion about this but the bottom line is that art and culture never were a priority for the Thai government. When we had a big film festival organized by the government, the budget was very high and it generated a lot of buzz. But the money came through the tourism authority – not the ministry of culture – and the goal was to promote tourism in the country and was focused on the red carpet gala instead of film culture. In a way, it was good for us to work on the programming side for the festival under this context though because we had absolute freedom in the film selection: the government officials provided the financing and never interfered in the programming at all. That’s not because they believed in artistic freedom but just because they didn’t care about it – they just needed film screenings to call it a film festival, no matter the films. They just wanted a red carpet gala premiere, that’s all! And it didn’t matter what film was screened as long as they could bring in any local celebrities, who have nothing to do with the film itself, to walk on the red carpet before the screening. And once the film started they’d all just leave for dinner instead.

What eventually happened with the Bangkok International Film Festival was very dramatic: it ended in the late 2000s following a corruption scandal that resulted in the then head of the Thai tourism authority being arrested and jailed for conspiring with an American company to receive bribes! It tarnished the reputation of the festival forever and the tourism authority stopped doing it altogether.

As far as film grants set up by the Ministry of Culture are concerned, it actually started off in a suspicious way too… Thai government usually prefers not to support arthouse films; they’d rather just support commercial productions. It’s just they had no choice but to support independent films since those are the films that are selected in international festivals.

The first edition of the grant was launched when the government had a plan to support a big-budget historical war epic from a commercial studio but they did it through the form of open-call grant instead, which raised a lot of eyebrows in the film community. When the grant application results were announced, it turned out that war epic project received something like 80% of the total grant money, with the 20% left split among 30 other projects or so – mostly independent arthouse projects. So the film community staged a protest against the unfair practice. And surprisingly, it worked – it usually doesn’t. The government revised the grant decision and reduced the support for that war epic and reallocated the money for more independent projects instead!

Afterwards, the grant program was continued on a yearly basis and played an important role in supporting a lot of Thai independent films for a decade – including Manta Ray. The amount is not big because the Ministry of Culture doesn’t receive a lot of budget from the government but it was helpful for local filmmakers. Later on, the grant program became less regular and eventually stopped at some point. There was no official explanation why it stopped – the Ministry of Culture would only say there is not enough budget for the given year while in fact it’s just never been a priority.

How would you define Thai cinema through the years?

Thai cinema has a very long history dating back to the late 1890s when the Lumiere brothers held their early screenings in Paris and has evolved a lot over the decades. But most films are not really known outside the country because it was only from the 1960s onward that Thai film started to get international recognition and were shown in international film festivals. Major influential filmmakers are RD Pestonji, whose 1961 film noir classic Black Silk was the first Thai film to screen at the Berlin International Film Festival, and Cherd Sonsri who made The Scar, a 1977 classic that remains one of the most popular Thai films of all time.

Then there was a long slump during the 1980s and early 1990s before a new golden age arose from the late 1990s onward with a new generation of filmmakers who revolutionized the industry – such as Nonzee Nimibutr (Dang Bireley’s and Young Gangsters, Nang Nak) and Pen-ek Ratanaruang (Fun Bar Karaoke, Monrak Transistor) followed by Wisit Sasanatieng, who made Tears of the Black Tiger which premiered at Cannes Un Certain Regard. Thai cinema culminated in the early 2000s with international success both in the commercial sector (with action and horror blockbusters) and in the arthouse scene (with Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films). Apichatpong’s success definitely helped spark a new wave and a new generation of independent filmmakers.

How do you see the future of Thai cinema?

Interesting question. I started my film career during the peak of the industry when Thailand had a big breakout with Ong-Bak, which became a major international success and launched the career of Tony Jaa, and also with a string of horror films that sold very well in the markets. The arthouse sector was thriving too with Thai films winning Cannes Jury Prize – and later our first Palme d’Or! But a decade later, it has changed a lot and there have been many ups and downs. On the industry side, I guess it’s partly because a lot of people are usually trying to emulate recent successes and flooded the market with the same type of films – following martial arts action blockbuster Ong-Bak’s international success, tons of martial arts action films poured in cinemas in the next few years. Same with supernatural horror films like Shutter, which sold well at film markets: in subsequent years, all the booths from Thai sellers at Cannes and AFM were only selling horror films! In the meantime, Arthouse films keep thriving in a way because there is still a steady stream of auteur-driven films being made that premiere at international film festivals every year.

However, filmmaking isn’t a very sustainable career as it’s very difficult to make a living from it. Many filmmakers had to stop and do something else at some point and then there’s a new generation of younger people coming up.

Apichatpong continues to be very successful in his career of course but he has stopped making films in Thailand now because he always had a problem with government censorship. And since the military coup in 2014 the situation got worse and it severely put a limit to what he – and most local filmmakers – can say and portray in films. Many filmmakers had to make films that are critical of the authority in a very abstract way in order to avoid censorship.

At the end of the day, Thai cinema has always strived on its own as there has always been hardly any support – and when there is, it always remains short-lived and irregular. There’s no such thing as a sustainable support system nor a recipe to success. A success today doesn’t guarantee anything in the long run. It’s only about surviving and bouncing back.

How has COVID-19 affected the movie industry in Thailand?

When we had the lockdown last year, all films productions were on hold and were only allowed to resume on the condition of strict health measures. Cinemas were closed for a period of time and attendance has dropped while fewer films were released too. So the distributors and exhibitors took a big hit. With the number of cases surging now, there is considerable economic ramification so it is getting even harder to find financing. The main effect might be the change in the audience behavior: people are now going to cinema less frequently and watch films on streaming platforms instead. For us this is difficult because given the kind of films we produce, we always prefer that people watch films in cinemas. It is a big challenge to overcome.

Interview by Françoise Duru