Mai Meksawan worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival since 2004, and was its programmer until the festival’s final edition in 2009.

...01 Jan 2025, 22:47

This content isn't available at the moment

When this happens, it's usually because the owner only shared it with a small group of people, changed who can see it, or it's been deleted.20 Jul 2023, 20:23

www.nyaff.org

Tickets go on sale this Friday at 12pm ET for the 22nd edition of the New York Asian Film Festival (NYAFF), presented by the New York Asian Film Foundation and Film at Lincoln Center (FLC), running fr...29 May 2023, 15:15

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell — Cercamon

www.cercamon.biz

After his sister-in-law dies in a freak motorcycle accident in Saigon, Thien is bestowed the task of delivering her body back to their countryside hometown. It is a journey in which he also takes his ...

Mai Meksawan worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival since 2004, and was its programmer until the festival’s final edition in 2009.

...

EVERY DAY A GOOD DAY is about a young woman’s induction into Japanese Tea ceremony over two decades. The movie is delivered

...

Hazel Orencio is a Filipino actress discovered by Lav Diaz in 2010. Her filmography includes Florentina Hubaldo, CTE (2012), Norte, The End

...

Mostofa Sarwar Farooki is a filmmaker and producer from Bangladesh. His first international breakthrough took place in 2009 with Third Person Singular

...

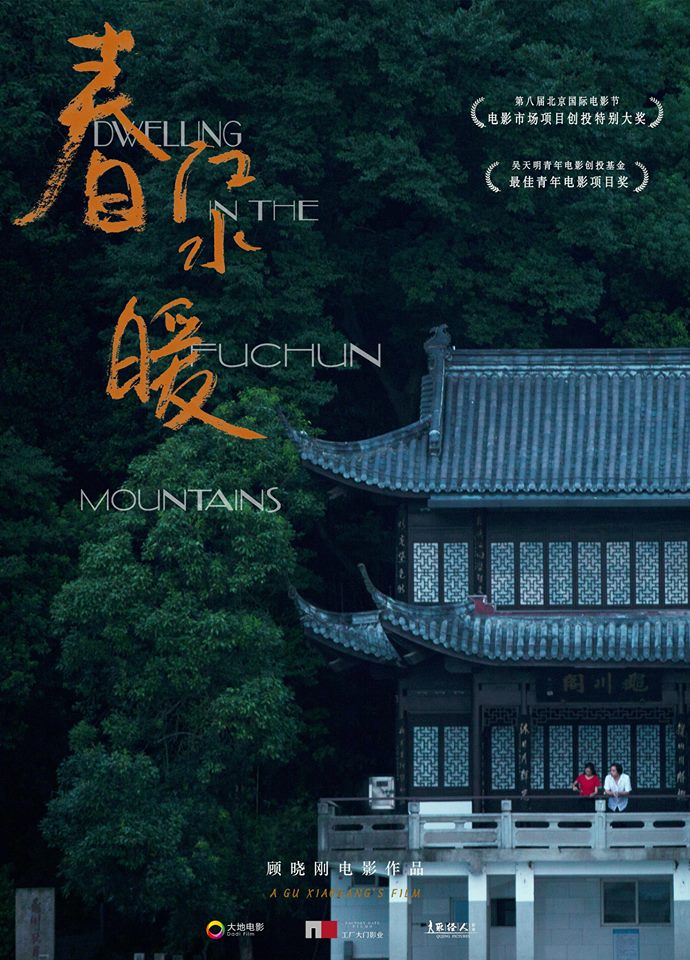

« Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains » (富春山居圖), Gu Xiaogang’s beautiful first feature film, which premiered at Cannes International Critics’ Week in

...

Thinley Choden is a producer and social entrepreneur from Bhutan. Her first film project was the Emmy Award winning documentary Bhutan: Taking

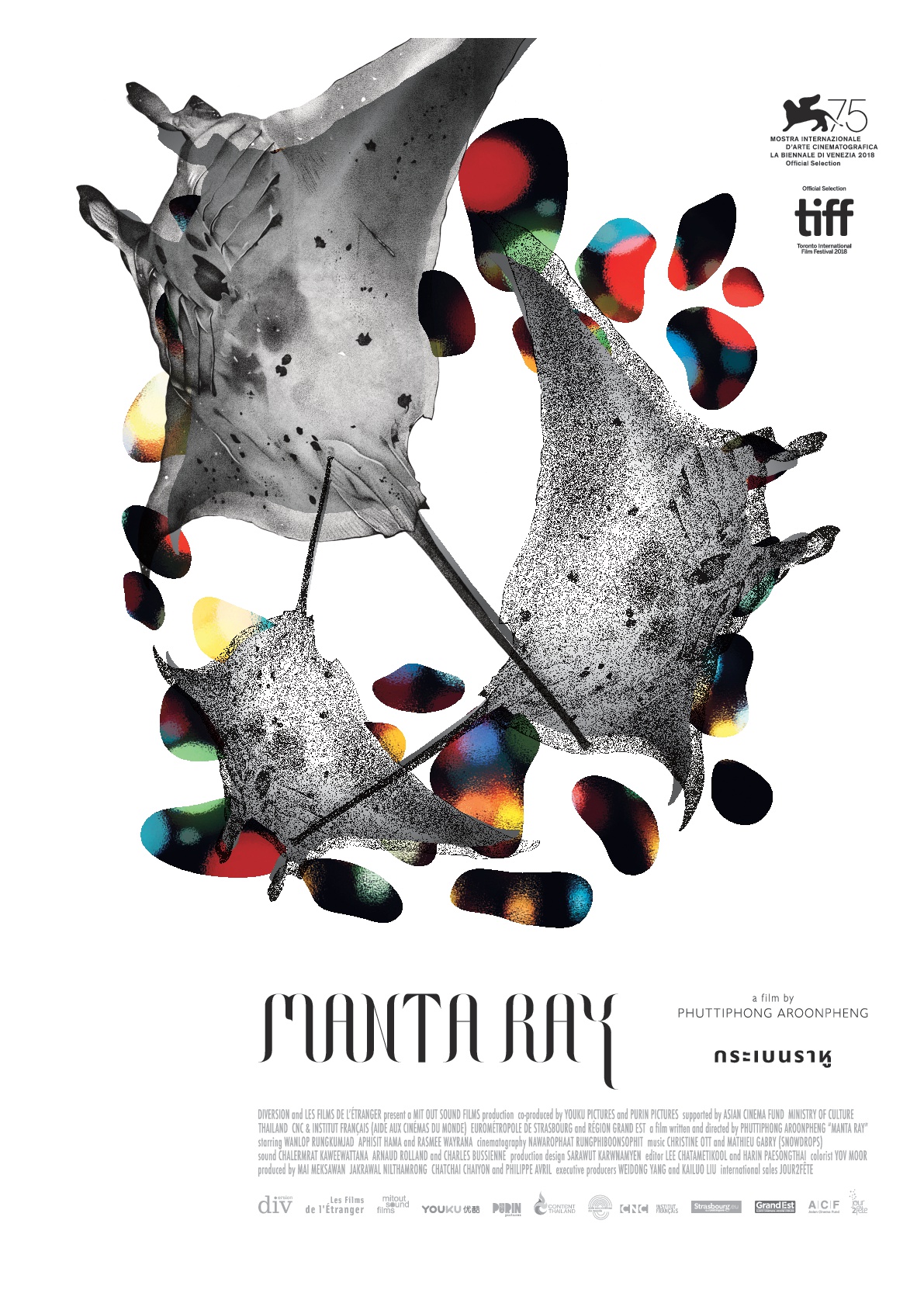

...Near a coastal village of Thailand, by the sea where thousands of Rohingya refugees have drowned, a local fisherman finds an injured man lying unconscious in the forest. He rescues the stranger, who does not speak a word, offers him his friendship and names him Thongchai. But when the fisherman suddenly disappears at sea, Thongchai slowly begins to take over his friend’s life – his house, his job and his ex-wife…

Winner of the Grand Prize in the Orizzonti section of the 2018 Venice Film Festival, MANTAY RAY, Phuttiphong Aroonpheng’s first feature, calls forth the shattered destiny of the Rohingyas through a mute character, symbol of this silenced and abandoned community. Never overtly mentioned, we can nonetheless hear the whisper of their voices accompanying the sound effects created by Snowdrop, a French electronic duo.

MANTA RAY

(กระเบนราหู, Kraben Rahu)

A film by Phuttiphong Aroonpheng

With Wanlop Rungkumjad, Aphisit Hama, Rasmee Wayrana

With Wanlop Rungkumjad, Aphisit Hama, Rasmee Wayrana

2018 – Thailand– Drama – 105 min – 1.85 : 1 – Sound 5.1 – Thai

| Screenplay: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (2.5 / 5) (2.5 / 5) |

Mai Meksawan worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival since 2004, and was its programmer until the festival’s final edition in 2009. He also programmed and co-organized several other festivals in Thailand. In 2007 he co-founded, with Pimpaka Towira and Ruengsang Sripaoraya, production and distribution company Extra Virgin, where its most successful title, Agrarian Utopia (dir. Uruphong Raksasad) screened in more than 100 film festivals worldwide and received 11 international awards. He founded production company Diversion in 2014. His most recent films as a producer include Manta Ray (dir. Phuttiphong Aroonpheng), winner of Orizzonti Award for Best Film at 2018 Venice Film Festival, Come Here (dir. Anocha Suwichakornpong), which premiered at Berlin Film Festival this year, and Anatomy of Time (dir. Jakrawal Nilthamrong), which is premiering at Venice Film Festival in the Orizzonti section right now.

What is your journey to film production? How did you end up becoming a film producer? What is your background?

I started my career as a festival organizer, working at the Bangkok International Film Festival which during most of the 2000s was Thailand’s main international film festival.

I studied architecture in university but have finally never practiced it – interestingly, similar to Apichatpong Weerasethakul as well. And I then happened to apply for a position at the Bangkok International Film Festival, first in the publicity department, and ended up there through the years. I was one of the programmers there during the festival’s latter years, until the government eventually stopped the funding and the festival was put to an end. During that time I got to know a lot of new up-and-coming filmmakers, the films of many of them we showed at the festival too and whom I ended up working with to help develop their projects. So as things progressed, I finally became their producer too. To be honest I can say that I did not set out to be a producer in the very beginning. It gradually happened in a natural and spontaneous way.

You produced Phuttiphong Aroonpheng’s Manta Ray. How did you meet him? What made you want to produce Manta Ray?

It was through another filmmaker I work with, Jakrawal Nilthamrong. I first met Jakrawal in 2008 or so when we started working together to develop his debut feature film project. He introduced me to Phuttiphong, who was his long-time friend as well as a veteran cameraman. Phuttiphong is the director of photography of Jakrawal’s short films too – as well as of his first narrative feature film Vanishing Point. During that time, we heard that Phuttiphong was also developing his own feature film project, titled Departure Day, as a director and so we decided to get on board. The project eventually became Manta Ray.

It was an interesting development. For a lot of other filmmakers I work with, they usually start off doing short films before evolving into feature films. The usual route for independent filmmakers in our region is spending their early years in their career making short films and sending them to festivals in order to build up their profile, which will help them land bigger fundings in order to make a feature film that will become their big breakout. But Phuttiphong took another path because he had an extensive experience in production, working as a cameraman and production designer for both independent and mainstream films. He did actually not make a lot of short films. He just had a very clear and focused idea of what he wanted to achieve in his debut feature film straight from the beginning – with a level of self-confidence that not a lot of first-time filmmakers can have.

What was the most difficult thing about producing Manta Ray? What was the budget of the film?

It was a bit over 400,000 Euros, which is quite high for a Thai independent film, especially for a first feature film. We were lucky to finally manage to get funding from China and France – respectively through Youku Pictures, which usually works with more commercial films, and through CNC’s Aide aux Cinémas du Monde (World Cinema Fund) and Strasbourg’s region fund.

The process was quite long and at times it felt quite uncertain how everything would eventually turn out. The long waiting period was perhaps the main challenge because Phuttiphong started the first draft of the script in 2009 and we ended up finishing the film in 2018. During that period though he actually also got married and started a family. There were also a couple of years in between when the project was put on hold because Phuttiphong was busy as a DoP for other films so we only officially resumed the project in 2016. The film ended up very different from the original script because in the beginning, when it was still Departure Day, Phuttiphong conceived it as a diptych – with a twin storyline where the first half of the film revolves around one set of characters in one location and the second half entirely with another set of characters and location altogether. And the two halves of the story are only interconnected in a loose and spiritual way. But later on, Phuttiphong decided to lift the first part of the story and turn it into a short film titled Ferris Wheel, which he completed in 2016. The short film was very well received and played a crucial role for us to get started and finally make the feature film, which is the second half of the story of the original script – about the fisherman who rescues a mysterious stranger, who turns out to be a Rohingya. It was quite a gamble but paid off very well. I think one benefit of the film taking a very long time to make is that, by the time we landed enough funding to actually get to start shooting, the project had been with Phuttiphong for so long that he already had a very clear picture in his head of what he wanted to do for each scene in the film. So when the time came for the actual shoot it went very smoothly.

Was the film released in Thailand? How did the audience react to it? Did the international audience react differently?

Manta Ray was released in Thailand in July 2019 – about ten months after the world premiere in Venice. By the time of the local release, it had extensively travelled in festivals and received several awards that helped a lot create buzz for the local press and audience. Given its specific form, the film mainly attracted local cinephiles, so we had a small but dedicated audience.

Regarding the difference between how local and international audiences perceived the film: the local audience tends to focus more on the cinematic style rather than the political context – from what we’ve seen. The international audience also tends to compare the film to the works of other Thai filmmakers they are familiar with, which I guess we cannot do anything about, whereas for the Thai audience, it’s almost the other way round since a lot of people here noticed that the film feels quite different from most Thai films.

What is it in general that makes you produce films? How do you choose your projects? Do you have a specific editorial line?

So far I mostly work with people I have a close relationship with or have known very well for a long time. Making films is a very long commitment and requires a lot of perseverance, so you really need to believe in it and in the people making it –a good relationship is crucial. Given my personal taste, I have really only worked on auteur-driven arthouse films. They are the kind of projects I like and make me want to get involved. Back when I organized film festivals I enjoyed both the curatorial aspect – the work as a programmer – and the logistics pertaining to managing budget, operations and people, which is pretty similar to producing films in a way. But the festival scene in Thailand is very troubled and when you do a festival here, it is the people who finance it who have the final say on everything. So after a while, I realized that it was never going to be something of my own. At the end of the day, it is always going to be somebody else’s festival you work for. And so I became more interested in producing because it allowed me to achieve something that I could truly call my own.

How do you finance an independent Thai movie as a producer?

In every way we can! Mostly through grants I suppose: a lot of Thai independent filmmakers who received recognition overseas rely a lot on supports through international – mostly European – subsidies like the Hubert Bals Fund, World Cinema Fund, CNC Aide aux cinémas du monde etc. We also used to have a local subsidy through the Thai Ministry of Culture’s annual film grant, which helped support a lot of Thai films that went on to have successful international festivals career over the past ten years. Unfortunately, the program has been suspended a few years ago. So we have to keep looking for new financing sources. Private equity financing is a big challenge because it is next to impossible for independent films to recoup investments (although that can be true for commercial films too). An overwhelming majority of local films released each year in Thailand lose money and only a small fraction break even or make a profit because the production and distribution costs are always very high while the distribution revenues are getting smaller year after year. It is an extremely risky business. I once had a conversation with a producer from a very big commercial studio, who said that we independent producers hold an enviable position in a way, because we are completely free from the commercial demands of the marketplace and can afford to produce the kind of films we want to do without having to worry that it will not break even and generate enough profit to recoup the financiers’ investments because that is never going to happen in the first place! Commercial producers need a commercial success for each of their films, which implies a severe limitation of what they can say or portray in their films because their career and whether they’ll be able to produce the next film are at stake. Independent producers do not have that kind of pressure because once a film is finished, we proceed to work on the next one right away no matter if the previous film is a box office success or not. As a result, independent films have much more freedom to tackle a much diverse range of topics too. I had not really thought about it this way before and it is quite an eye-opening statement. It is not our intention of course to only make films for festivals and critical recognition without generating enough commercial income for our financiers because that won’t certainly be a viable business model in the long run but at the same time it is important that everyone is realistic and has the same expectation of what will be the place of the film, once it is finished, in the marketplace – what level of commercial results it could generate and what kind of exposure it will get. We always need to make sure we work with partners, who share this same understanding, which is of course never easy and limits our options a lot. But we have to keep looking.

What are your upcoming production projects?

We completed Anocha Suwichakornpong’s new film, Come Here, which premiered in Berlin earlier this year. It is her official third film following Mundane History and By The Time It Gets Dark, and it is generating good interests in the festival circuit. We’re also very proud to present Jakrawal Nilthamrong’s Anatomy of Time at Venice Film Festival. It is our biggest and most ambitious project so far, and also our first multi-territories co-production too – with co-producers from France, The Netherlands and Singapore. Jakrawal’s background is in visual arts and his works are usually very experimental and non-narrative with major influence from Buddhism. But for this project it is comparatively more narrative than his other works and we are very excited about it. Another one is Uruphong Raksasad’s Worship, which is a mix of documentary and fiction. Uruphong usually likes to explore the boundary between reality and fiction and his works always revolve around the lives and hardships of villagers in Thai countryside with strikingly beautiful cinematography that hides a dark hinge of melancholy. He is also now getting more political – which is quite natural given the way the Thai political situation is heading over the past year, where a lot of people are getting much angrier and outspoken – and the film also reflects this collective sentiment but in a more subtle way. We are also developing a new feature project by a first-time director Patiparn Boontarig. We have been working with him for a very long time as he is the First Assistant Director of Phuttiphong’s and Jakrawal’s films. The title is Solids by the Seashore and revolves around an intimate relationship between two young women in the south of Thailand – a predominantly Muslim region that is very culturally different from the rest of Thailand, which is long known as a Buddhist country. The south is also famous for tourism with its long stretches of coastline but has been suffering from worrying environmental damage over the years with the sea erosion. The local government has built a series of concrete seawalls to stop the erosion, which permanently damaged the beaches and ended up causing more erosion in different directions. The film also reflects on this issue and speaks about human’s ultimate failure at fighting nature and repeatedly trying to control the world they are living in. Lastly, we are working further on Phuttiphong’s new film Morrison. It is a more ambitious project and speaks about a subject that is totally different from his previous work – it’s about the collective memory of Vietnam war in Thai society and rock & roll music. But it retains Phuttiphong’s signature style of filmmaking with the similar atmospheric feel of Manta Ray but in a different direction.

How many independent/arthouse films are produced every year? How many are theatrically released in Thailand (in normal times)?

The independent scene here is active but I’m not fully sure about the exact number. Maybe something like 5-10 new films each year. Most of the independent films are actually released in cinemas here because most of the time the filmmakers self-release their films and directly talk to cinemas. Theatrical remains the principal way for Thai independent films to be seen by the local audience since there is virtually no DVD market anymore and arthouse films are usually not available on streaming. I guess one benefit of Thailand is that local cinemas are very open to release independent films so filmmakers can deal directly with exhibitors without the need of a distributor. But the catch is that the release can end up to be extremely limited: most independent movies would only get released on 2-3 screens – with only 1 screening a day and up to 2 screenings during weekends. So it is very limited. And cinemas can be very quick to remove the titles that do not perform well commercially within the first few days of release. So the films may be shown in cinemas for only 2 weeks maximum or even less than that. At the end of the day, they can be gone very quickly.

There are about 50 films (all genres and budgets) released per year, meaning one new local film released each week.

Since COVID, there has not been a lot of new independent films released in cinemas though.

How many movie theatres are there in Thailand?

There are two rival chains of multiplexes that dominate the market. Together they account for about 1,000 screens – one chain holding 60% and the other 40%. These chains do screen arthouse films too but in a very limited format as described above.

As far as arthouse cinemas are concerned, there are only two of them – all in Bangkok. And one of them actually closed last year due to the impact of COVID-19. So now we only have one 3-screen arthouse cinema left, so it is vastly underserved for a big city like Bangkok. Technically there is also another independent cinema in town although they do not screen DCPs. It also closed down this year due to the pandemic again but it has recently been taken over by a local independent distribution company that will keep the venue running and continue the screening program, which is good news.

That main arthouse cinema is “House Cinema”, which is Thailand’s first cinema dedicated to arthouse films. It is owned by Sahamongkolfilm, which is the country’s biggest distributor. They started to release arthouse films in the late 1990s because at the time they bought a lot of films in bundles from sales agents and needed to have an outlet to release them and eventually opened their own cinema. The other arthouse cinema was the Apex cinema chain, which operated the country’s last surviving standalone cinemas – they had three cinemas in the city center (Siam, Lido and Scala). After the emergence of shopping mall multiplexes, Apex switched their programming to focus on independent films, which became very popular. But it is very difficult to operate a standalone cinema in addition to a number of other factors too: the Siam was burned down during the violent crackdown by the military during the red shirt demonstration in 2010. The Lido closed down in 2018 when its landlord decided not to renew the lease and then the final nail in the coffin took place last year when the Scala had to close down because of the economic impact of COVID-19.

There was also the Bangkok Screening Room, which had been in business since 2016. It was also an independent cinema. It did not screen DCP though. It was affected by COVID-19 too and closed down at the end of March 2021. But fortunately, it is taken over by a local distribution company, Documentary Club, which will keep the cinema running.

There is no arthouse cinema in other cities so far. There are certainly growing arthouse audiences in many places but the market remains limited and it is obviously very expensive to operate a cinema. In cities like Chiang Mai, Khon Karen or Hadyai, where there are active university students communities, there are many audiences who are curious about independent films but the films would only screen in non-cinema venues instead such as local art galleries, bookshops or cafes. The screening quality is not high but it’s become the only way for these films to be seen there.

Streaming has changed a lot in terms of audience habits. Nowadays – and even before COVID-19 –, cinema attendance has dropped and the audience is actually becoming more accustomed to watching content online rather than on the big screen. It’s a development that is especially challenging for us given what we do.

Are there many film festivals in Thailand? What kind of audience do they address?

Actually, there is practically none nowadays. Back when I worked at the Bangkok International Film Festival, we had two international film festivals showing arthouse films from Cannes, Venice and Berlin, which attracted a significant local audience (film lovers, students, young professionals, international communities etc.). And there was also a number of smaller thematic festivals through the year – about 1 or 2 every month – so the scene was quite active. But over the years, it has become harder and harder for festival organizers to keep afloat. A lot of festivals, including the one I worked with, had to end at some point. It’s an unfortunate reality.

Why aren’t there any film festivals and film grants in Thailand anymore?

It is a complicated issue and we can have a very long discussion about this but the bottom line is that art and culture never were a priority for the Thai government. When we had a big film festival organized by the government, the budget was very high and it generated a lot of buzz. But the money came through the tourism authority – not the ministry of culture – and the goal was to promote tourism in the country and was focused on the red carpet gala instead of film culture. In a way, it was good for us to work on the programming side for the festival under this context though because we had absolute freedom in the film selection: the government officials provided the financing and never interfered in the programming at all. That’s not because they believed in artistic freedom but just because they didn’t care about it – they just needed film screenings to call it a film festival, no matter the films. They just wanted a red carpet gala premiere, that’s all! And it didn’t matter what film was screened as long as they could bring in any local celebrities, who have nothing to do with the film itself, to walk on the red carpet before the screening. And once the film started they’d all just leave for dinner instead.

What eventually happened with the Bangkok International Film Festival was very dramatic: it ended in the late 2000s following a corruption scandal that resulted in the then head of the Thai tourism authority being arrested and jailed for conspiring with an American company to receive bribes! It tarnished the reputation of the festival forever and the tourism authority stopped doing it altogether.

As far as film grants set up by the Ministry of Culture are concerned, it actually started off in a suspicious way too… Thai government usually prefers not to support arthouse films; they’d rather just support commercial productions. It’s just they had no choice but to support independent films since those are the films that are selected in international festivals.

The first edition of the grant was launched when the government had a plan to support a big-budget historical war epic from a commercial studio but they did it through the form of open-call grant instead, which raised a lot of eyebrows in the film community. When the grant application results were announced, it turned out that war epic project received something like 80% of the total grant money, with the 20% left split among 30 other projects or so – mostly independent arthouse projects. So the film community staged a protest against the unfair practice. And surprisingly, it worked – it usually doesn’t. The government revised the grant decision and reduced the support for that war epic and reallocated the money for more independent projects instead!

Afterwards, the grant program was continued on a yearly basis and played an important role in supporting a lot of Thai independent films for a decade – including Manta Ray. The amount is not big because the Ministry of Culture doesn’t receive a lot of budget from the government but it was helpful for local filmmakers. Later on, the grant program became less regular and eventually stopped at some point. There was no official explanation why it stopped – the Ministry of Culture would only say there is not enough budget for the given year while in fact it’s just never been a priority.

How would you define Thai cinema through the years?

Thai cinema has a very long history dating back to the late 1890s when the Lumiere brothers held their early screenings in Paris and has evolved a lot over the decades. But most films are not really known outside the country because it was only from the 1960s onward that Thai film started to get international recognition and were shown in international film festivals. Major influential filmmakers are RD Pestonji, whose 1961 film noir classic Black Silk was the first Thai film to screen at the Berlin International Film Festival, and Cherd Sonsri who made The Scar, a 1977 classic that remains one of the most popular Thai films of all time.

Then there was a long slump during the 1980s and early 1990s before a new golden age arose from the late 1990s onward with a new generation of filmmakers who revolutionized the industry – such as Nonzee Nimibutr (Dang Bireley’s and Young Gangsters, Nang Nak) and Pen-ek Ratanaruang (Fun Bar Karaoke, Monrak Transistor) followed by Wisit Sasanatieng, who made Tears of the Black Tiger which premiered at Cannes Un Certain Regard. Thai cinema culminated in the early 2000s with international success both in the commercial sector (with action and horror blockbusters) and in the arthouse scene (with Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films). Apichatpong’s success definitely helped spark a new wave and a new generation of independent filmmakers.

How do you see the future of Thai cinema?

Interesting question. I started my film career during the peak of the industry when Thailand had a big breakout with Ong-Bak, which became a major international success and launched the career of Tony Jaa, and also with a string of horror films that sold very well in the markets. The arthouse sector was thriving too with Thai films winning Cannes Jury Prize – and later our first Palme d’Or! But a decade later, it has changed a lot and there have been many ups and downs. On the industry side, I guess it’s partly because a lot of people are usually trying to emulate recent successes and flooded the market with the same type of films – following martial arts action blockbuster Ong-Bak’s international success, tons of martial arts action films poured in cinemas in the next few years. Same with supernatural horror films like Shutter, which sold well at film markets: in subsequent years, all the booths from Thai sellers at Cannes and AFM were only selling horror films! In the meantime, Arthouse films keep thriving in a way because there is still a steady stream of auteur-driven films being made that premiere at international film festivals every year.

However, filmmaking isn’t a very sustainable career as it’s very difficult to make a living from it. Many filmmakers had to stop and do something else at some point and then there’s a new generation of younger people coming up.

Apichatpong continues to be very successful in his career of course but he has stopped making films in Thailand now because he always had a problem with government censorship. And since the military coup in 2014 the situation got worse and it severely put a limit to what he – and most local filmmakers – can say and portray in films. Many filmmakers had to make films that are critical of the authority in a very abstract way in order to avoid censorship.

At the end of the day, Thai cinema has always strived on its own as there has always been hardly any support – and when there is, it always remains short-lived and irregular. There’s no such thing as a sustainable support system nor a recipe to success. A success today doesn’t guarantee anything in the long run. It’s only about surviving and bouncing back.

How has COVID-19 affected the movie industry in Thailand?

When we had the lockdown last year, all films productions were on hold and were only allowed to resume on the condition of strict health measures. Cinemas were closed for a period of time and attendance has dropped while fewer films were released too. So the distributors and exhibitors took a big hit. With the number of cases surging now, there is considerable economic ramification so it is getting even harder to find financing. The main effect might be the change in the audience behavior: people are now going to cinema less frequently and watch films on streaming platforms instead. For us this is difficult because given the kind of films we produce, we always prefer that people watch films in cinemas. It is a big challenge to overcome.

Interview by Françoise Duru

(2.8 / 5 While a somewhat academic journey into the Way of Tea, Omori's rite-of-passage drama is a beautiful ode to the late Kirin Kiki (The Shoplifters, Sweet Bean) whose poise and grace, as the tea ceremony master, definitely compels our admiration.)

(2.8 / 5 While a somewhat academic journey into the Way of Tea, Omori's rite-of-passage drama is a beautiful ode to the late Kirin Kiki (The Shoplifters, Sweet Bean) whose poise and grace, as the tea ceremony master, definitely compels our admiration.)EVERY DAY A GOOD DAY

(日日是好日, Nichinichikorekojitsu)

A film by Tatsushi Omori

With Kirin Kiki, Haru Kuroki and Mikako Tabe

With Kirin Kiki, Haru Kuroki and Mikako Tabe

2018 – Japan – Drama – 100 min. – Aspect ratio 1.85:1 – 5.1 Sound – Audio: Japanese

World premiere: Busan Film Festival 2018

| Screenplay: |  (2.0 / 5) (2.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

EVERY DAY A GOOD DAY is about a young woman’s induction into Japanese Tea ceremony over two decades. The movie is delivered by Tatsushi Omori in a light and refreshing fashion that reflects a most distinctive vein of Japanese cinema and provides an opportunity to dwell on the meaning and the origins of the ancient art of tea a.k.a. the Way of Tea.

In Japanese, certain words that are commonly used in everyday life have no equivalent in Western languages such as « Tadaima » (只今). When Japanese people would return to their home, they would often call out the word, “Tadaima”, as a greeting. The word means, “I‘m home” or more literally “Now (here)”. The person already inside would reply: « Okaeri » (お帰り), meaning “Welcome home”, but more literally, “(You are) returning home”. Similarly, “Otsukaresama” (お疲れ様) – which, in plain form, means “to be tired” – is used at the end of a workday between colleagues to show each other support. As a matter of fact, recognizing someone is tired can be read as, “you are tired because you have worked hard, so thank you”.

Thus, learning Japanese language – especially for a Western individual – boils down to questioning our very reflections on everyday life beyond traditional popular exotic imagery. Or else misunderstandings can occur, especially when it comes to abstract words. In Japanese history, slavery for instance never was a common practice. As a result, can we assume the English word « Freedom » and its Japanese equivalent « Jiyū » (自由) actually have the same meaning, the same nuances? Similarly, does the English word « Mind » and its Japanese equivalent « Kokoro » (心) share the same reality when in Japanese culture the mind and the body can not be conceived separately?

Those linguistic realities merely highlight different reference systems when it comes to ideas and concepts, based on different histories, values and ultimately cultures. This explains why many activities or practices exist in Japan only. What is commonly referred to as the Tea Ceremony being one of them.

With a history of more than 500 years, the tea ceremony unfolds according to a specific etiquette that has remained unchanged over the years: a tea master hosts up to five guests in a room with a hearth built into the floor then serves matcha – a slightly bitter and creamy green tea ground into powdered form (the green tea powder being whisked into hot water, instead of steeped, to form a frothy drink). After watching the host prepare the tea, guests are expected to eat sweets that are served to them before the tea is drunk. The host then cleans the utensils in preparation for putting them away – the guests may in turn examine some of the utensils to show respect and admiration for the host. The items (tea bowl, caddy, scoop, whisk) are treated with extreme care and reverence as they may be handmade antiques.

The word “ceremony” frequently used to describe the Japanese ritual may be misleading since it is unrelated to any religious practice. Nor does it commemorate any specific event or holiday. The ceremony can be performed at any time of the year and at all times of the day. There is no hidden meaning in the gestures performed by the tea master, which may eventually be very similar to those performed by anyone preparing matcha tea at home. At the end of the day, it’s nothing more than boiling water, making tea and drinking it!

The difference actually lies in the gestures, postures and movements performed by the tea master that need to comply with a set pattern named kata (形). Sitting on the tatami mat floor, using and placing every utensil, transferring hot water from the pot to the bowl and mix it with tea powder – every gesture and movement is as deliberate as graceful. There is no room for improvisation. Even the guest is supposed to drink tea according to a specific etiquette. There is no denying the tea ceremony requires full attention and focus from its participants – at the end of the day, it does actually meet the attributes of a ceremony.

In Japanese, this cultural practice is known as Sadō (茶道), literally meaning the Way of Tea. The Way is a term used to denote the fundamental principle underlying a system of thought or belief, an art, or a skill. It is also used by extension to refer to the entire body of principles and skills that constitute an art. In this latter sense it is used in Japan as part of the name of a number of traditional skills or codes of behavior, as in Kadō (華道) for flower arrangement, Shodō (書道) for calligraphy, Kendō (剣道) for fencing, Kyudō (弓道) for archery, Judō (柔道, literally “the Way of Flexibility”), Kodō (香道) for the art of incense appreciation etc.

The activities mentioned above are neither considered as mere physical activities nor intellectual activities alone. The body and the mind complement each other, the Way thus addressing both concepts. The basis of the Way, resides in posture and body movement – both performed in a physical and mental fashion. These are related to an etiquette that forms a correct attitude toward life and reflects a deep inner focus.

If all ways relate to different practices, they all follow specific numbers and sets of katas – the very nature of which is inherent to the world they belong to. In that prospect, ways are nothing but activities defined by specific movements and postures1(1) Within a specific way, katas may vary according to schools or styles. However, each way acknowledges the katas they rely on only.. Practicing a way doesn’t require any theoretical teaching: it only requires the practitioner to be inducted by a master through the performance of katas that are inherent to that specific way. Repeating the katas until they are performed with confidence and grace being the ultimate goal.

The performance of katas is actually subject to certain external conditions: in martial arts, they depend on the opponent’s moves; on stage, they depend on the character types and moods; in the Way of Tea, they reflect the changing seasons. Tea ceremony in the summer and winter are not the same as in every season many aspects of the ceremony change including the state of mind.

Does the Way of Tea lead to a specific place?

The practice of Ways culminated in the Edo period (1603-1868) but they are actually rooted in the Muromachi period (1336-1573). However, those practices existed way before they were called ‘ways’.

As a matter of fact, although the Way of Tea is considered to have been founded by the monk Murata Jukō (1422-1502), the tea drinking ritual dates back to much more ancient times2(2) The ritual is said to date back from the 13th century – warriors practiced zen meditation then before it became some kind of leisure, consisting of appreciating both the quality of utensils used during the ceremony and the origin of the served matcha. The whole process was progressively codified starting from the 15th century and the ritual itself became as important as the drink.. The influence of Buddhist philosophy on the Ways during the Feudal period explains how they are perceived today.

Buddhism’s core teaching acknowledges that the root of all suffering is attachment: we want things to be while they are constantly changing. Our suffering influences our actions (karma), poisons them in a way so that we’re aimlessly wandering – forever lost in a circle of birth, rebirth or redeath (samsara). Buddhism considers that we reincarnate – reincarnation being defined as the re-embodiment of an immaterial part of a person after a short or a long interval after death, in a new body whence it proceeds to lead a new life in the new body more or less unconscious of its past existences, but containing within itself the “essence” of the results of its past lives, which experience goes to make up its new character or personality. In this context, the Way is the practice of non-attachment, i.e. meditation, in order to escape the cycle of reincarnation of Samsara and eventually achieve Nirvana.

In practice, it is less about renouncing material things than becoming aware of their emptiness (things don’t exist by themselves and are consequently ephemeral) and of our selves (“I” only exist with respect to everything else). That awareness is called awakening – in Japanese: satori (悟り).

Since its origins, Buddhism has been divided into many schools of thought, which distinguish from each other either through a specific system of practices or through a different philosophical approach. According to Robert Heinemann(33) An expert in Japanese Buddhism, Robert Heinemann created the Japanese Studies chair at the University of Geneva where he was an honorary professor from 1980 to 1993. Audio recordings of his lectures and classes are available on the website of the university., if “some forms of Indian Buddhism represent the path to salvation as a journey that releases us from a painful existence […] ou as a kind of disintegration of our mental structures […], Far East Buddhism, and more specifically Japanese Buddhism, underlines that Samsara and Nirvana are not distinct but one while different. Deliverance is achieved inside Samsara and our torments: we can be awakened without undermining our mental structure”4(4) Heinemann, Major controversies in the history of Japanese ideas (https://mediaserver.unige.ch/play/56876, in French starting from 07:40).

The idea that enlightenment is not reached by practicing a gradual series of meditations with a beginning and an end, but is achieved here and now in our material world, has contributed to the emergence of new schools of thought including Zen Buddhism. According to them, we can detach ourselves from things and the suffering they cause by becoming aware of their emptiness at every moment of our thoughts. The path thus redefined no longer leads to a goal but is identified with a practice according to which awakening is achieved in the succession of moments. If there is deliverance, it takes place in the very flow of our thoughts.

The zen philosophy refers to this type of thinking as non-thinking (無心, Mushin). The word is not to be taken in the sense of an empty thought, but of a detached thought, slipping over all things without ever settling on them. In other words, it is not a question of thinking of nothing but of “thinking of all objects without being infected by them (…): at each moment of thought, we free ourselves from the constraints that we impose on ourselves by the thought of the previous moment. »5(5) Heinemann, Japanese Buddhism – a philosophy of nothingness (https://mediaserver.unige.ch/play/56799, in French starting from 37:40). Each moment of thought is lived fully for itself, as if it alone carries the sum of all the moments.

Known for having completed the codification of Noh (能, Nō) theater, Zeami (1363-1443) is considered the first layman to have reinterpreted the unfolding of ancient practices (in this case, dances and songs performed in the open air) in the light of Buddhist philosophy. He considers indeed that each gesture must be carried out for itself according to the principle of the non-thought and is also the first to propose a theory of the katas and to set as a goal a level of ease or freedom from which the spirit of the practitioner does not cling to anything any more once those katas perfectly mastered. In Zen, this state is compared to water which, having no color, shape, or taste, make take on all colors, shapes, and tastes, depending on the circumstances to which it is subjected.

The Way of Tea as it is practiced today is essentially the outcome of the conceptions bequeathed by Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591) in the continuity of Buddhist thought. His teaching revolved around the adage “one life, one encounter” (一期一会, ichi-go ichi-e), which is about understanding “everything must be done as if it were done only once in a lifetime”6(6) Heinemann, The Way and the Ways in Japan (https://mediaserver.unige.ch/play/56837, in French starting from 31:50). Each gesture, each meeting, each day represents an instant, or a series of instants, the particular circumstances of which only occur once in relation to all possible moments. Each moment opens up to the totality: it is about treasuring the unrepeatable nature of a specific moment.

Opposed to the pomp and ostentation of certain tea meetings of his time, Rikyu advocated simplicity and simplicity according to the codes of the wabi-cha style (わび茶), both in the shape of the utensils used and in the layout of the room where tea is served7(7) The opposition between those two styles is displayed in the movie Love Under The Crucifix (1962) by Kinuyo Tanaka.. Reduced to a cramped surface (three or even two and a half mats), the room merely displays a floral composition or a calligraphy as decoration. Nothing more.

When practicing the Way of Tea, focus must remain total: the slightest drop of water poured, the slightest crumpling of tissue, the breathing itself participate in the course of the activity. It is at this price that the gestures, repeated over and over again, can be embraced by the personality of the practitioner and that the latter, over the course of days, seasons and encounters, can become aware of the purity of each moment and become one with them.

Like all ways, the Way of Tea is to be considered from the perspective of Buddhist practice and the search for enlightenment – which is summed up in the very title of Tatsushi Omori’s movie: Every Day is a Good Day.

Nicolas Debarle

A specialist of Japanese cinema, Nicolas Debarle is the author of many articles and festival reports published through internet (French online magazines Il était une fois le cinéma, EastAsia). He teaches French in Tokyo where he has been living since 2012.

Hazel Orencio is a Filipino actress discovered by Lav Diaz in 2010. Her filmography includes Florentina Hubaldo, CTE (2012), Norte, The End of History (2013), Prologue To The Great Desaparecido (2013), From What Is Before (2014), A Lullaby To The Sorrowful Mystery (2016), Season of the Devil (2018), The Halt (2019)… While acting in Lav Diaz’s films, she has quickly over time taken a pivotal role in Sine Olivia Pilipinas, Diaz’s production company.

As a student, you chose to embrace theatre. Is it what you always wanted to do? What was your motivation then?

I’ve always wanted to become a stage actress ever since. My Uncle, who is a painter, used to bring me to his school when he was in college and he will take me to watch stage plays. Since then, I told myself I wanted to become an actress.

Looking at the photos of the actors in the playbill, I remember I was 8 or 9 years old then and we’ve watched a fantasy children’s play, and I told myself, someday, I want my photo to be seen also in playbills. I thought acting is a really cool job. I want to dress up and play different roles.

How and when did your collaboration with Lav start as an actress?

I auditioned for the role Gregoria De Jesus (Prologue To The Great Desaparecido, A Lullaby To The Sorrowful Mystery) in 2010. I was asked to go to the studio of the director for a go-see upon the recommendation of our theater director, Adriana Agcaoili. I went, and there was the casting director, who introduced himself as Romeo Lee, and his then-camera assistant, Willy Fernandez. The casting director said we should wait a bit for Lav because he was stuck in traffic. I waited with them, and then they asked me to study the script while waiting. Afterwards, the casting director said the director can’t make it and that we should proceed. They made me read lines in the script. After that, I went home. And then I was left wondering what kind of audition was that; a director not making it in the audition because he was stuck in traffic. I didn’t know what Lav looked like so I immediately searched online and when I finally realized he was with us all along – « Romeo Lee »! –, I was embarrassed! So I didn’t really expect to get the role at all, but then I got a follow-up text asking me to attend the second call. I nearly went to the studio with a costume, just to make up for my mistake of not knowing how Lav looked like. But then, when I arrived, they were already having a party. The party was for me, because they said I got the role. I was very shocked… That’s how I met Lav! [Laughs]

Having now worked on not far from 10 films with Lav as an actress, what would you say is unique about Lav’s directing his actors/actresses? How would you define his directing style?

We are most free with Lav. We are free to do anything as long as it is in character. Shooting films with Lav is doing a collaborative work and he really considers our inputs as actors to the script that he’s writing (he writes the script every shooting day). He really acknowledges everyone’s participation, not just the actors but also the crew, and never fails to thank everyone on the set every day. That kind of importance that he gives to everyone matters a lot. He is never the type to take the credit of the merits of the film all to himself; it is always a collaborative work for him. For example, for Century of Birthing, a film with absolutely no script from the beginning, Lav just told me my role is a mad, pregnant woman. During my first scenes, I started doing movements for the role and also hummed a tune and Lav connected the tune to a song my character used to sing when she was still sane, which later on became the famous “Amang Tiburcio Song” which was sung frequently in the film.

What was the hardest scene and/or role you played?

Every role is hard; every film, every role is a challenge. When working with Lav, we will always be challenged and we will always be taken out of our comfort zones, all the more since Lav is a one-take director. One of the scenes I remember that were specifically hard was Gregoria De Jesus’ confrontation scene with Cesaria Belarmino in A Lullaby To The Sorrowful Mystery. I play Gregoria De Jesus, searching for her husband Andres Bonifacio’s missing body. And in that scene Cesaria Belarmino (played by Alessandra de Rossi) confesses she is the reason for the collapse of Andres Bonifacio’s rebellion. She is the reason of the execution of Gregoria De Jesus’ husband. I (the character) was so mad, I gave my all at that scene to the point I actually had a blackout when I did that scene. I was so blown away that I was literally eaten up by anger so I fell before I got up again and went for the big rock! I was practically shaking after that scene! I remember watching the film and that scene in Berlin – the film was in Official Competition at Berlinale 2016. Alessandra and I were holding hands, crying. It wass like we were not the ones acting on screen. It’s a memorable scene for me.

Can you tell us more about your role in Prologue To The Great Desaparecido ?

I play Gregoria De Jesus, the wife of Philippine hero Andres Bonifacio. Gregoria De Jesus is the wife of Andres Bonifacio – a hero who didn’t die in the war but whose execution was ordered by his comrade. His body was never found.

As with most of Lav’s film, it just took us a week to shoot it, and two weeks in preparation. To prepare for the role, I remember reading Santiago Alvarez’s “Katipunan and The Revolution”. Since it is written like a diary type, I was reading chapter per chapter so that I take the emotion on the next day when we shoot.

While reading the book, I intentionally did not sleep nor wash, in order not to lose the feeling, the momentum. Gregoria De Jesus searched for Andres Bonifacio’s body in the mountains for thirty harrowing days.

Have you ever contemplated acting in other filmmakers’ films?

I appeared in some of the films of other directors like Ron Bryant ( Bingoleras ) and Paul Soriano ( Duko ). It is different because with those two films, there’s already a script prior to shooting and all we had to do is execute the script line per line, word by word. It is a breath of fresh air, I would say, working with different directors but it is a totally different set-up mainly because these productions have plenty of crew with them (around 70-100 people) and a lot of equipments compared to Lav’s skeletal team and minimal equipment and very organic process. I am open to working with other directors but I see to it that the directors are very open with discussions. But for now, since Sine Olivia is a small company with only me and Lav running it, I am very loaded with work so I really don’t have time to accept other roles from other films/directors.

You’re also credited as an assistant director, production manager, casting director, editing assistant, post production supervisor, costume designer, production designer, location scout in many of Lav’s films.

I love all of my positions! Multi-tasking is something I was trained to do in theater. When I was a part of the chorus in theater, I was also a wardrobe assistant and an assistant production manager. I love the adrenaline high that I’m getting doing all the production works. I did that for a friend, Mac Alejandre, back in 2018 for the film Kaputol, but I don’t want to do it again for other filmmakers. I’d only do it for Lav.

If you were to choose between acting and working in production, what would you ultimately choose and why?

Acting. Whenever we shoot, it is when I act that I get to “rest”; I get to be in a different world, in a different spectrum. It’s like I am living a different life apart from mine. There are many roles I wish to do, so many characters, but I can’t play all of them in my lifetime. So I am dedicating my life to acting (but still doing production work on the side). I won’t stop.

What was/were the most difficult obstacle(s) you ran into during production?

I think those times when actors and crew members back out last minute, or a family member of an actor dies and we have to replace him last minute. It’s really hard to get a replacement.

Political pressure is also among the reasons actors sometimes had to back out… It’s not simple…

How would you describe the movie industry in the Philippines?

It is vibrant, I have to say. We have a lot of creative filmmakers here. But sadly, like everywhere else I guess, the distribution system is cruel like if a film isn’t earning much during its commercial run, it is being pulled out in theaters. The only hope of films being shown/showcased is through local film festivals and streaming platforms. The government isn’t also helpful also with this kind of system. In fact, to be able to screen a film, you would have to deal with a lot of bureaucratic permits and payments. This is why despite the acclaims of Lav’s film, they rarely get shown here in the Philippines…

Exclusive: PROLOGUE TO THE DESAPARECIDO by Lav Diaz is available to stream for free until June 5, 2020 in the WHAT’S ON section!

Interview by Françoise Duru

(3.5 / 5 A social feminist film that questions women's empowerment in a country with long-time patriarchal traditions and simultaneously highlights the ruthless capitalistic logic serving developed countries...)

(3.5 / 5 A social feminist film that questions women's empowerment in a country with long-time patriarchal traditions and simultaneously highlights the ruthless capitalistic logic serving developed countries...)MADE IN BANGLADESH

(মেড ইন বাংলাদেশ)

A film by Rubaiyat Hossain

With Rikita Nandini Shimu, Novera Rahman, Deepanita Martin

With Rikita Nandini Shimu, Novera Rahman, Deepanita Martin

2019 – Bangladesh/Denmark/France/Portugal – Social drama – 95 mins – Color – Aspect ratio 1.85:1 – 5.1 Sound – Audio: Bengali

International distribution: Pyramide International

| Screenplay: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

Mostofa Sarwar Farooki is a filmmaker and producer from Bangladesh. His first international breakthrough took place in 2009 with Third Person Singular Number (Bengali: থার্ড পারসন সিঙ্গুলার নাম্বার ) featuring Nusrat Imrose Tisha in her acting debut. The film premiered at Busan International Film Festival then was presented in Europe at Rotterdam International Film Festival.

Farooki’s following feature film Television was chosen as the Closing Film of Busan International Film Festival in 2012.

“A key exemplar of Bangladeshi new wave cinema movement” according to Variety, festival darling Farooki has just received two prizes at Vesoul International Film Festival of Asian Cinema for his film Saturday Afternoon (Shonibar Bikel), which is banned in Bangladesh.

How did you become a filmmaker? What was your journey toward filmmaking?

I really don’t recall when it all started. I was brought up in a typical middle class neighborhood named Nakhalpara in Dhaka. People from this area have a great storytelling tradition. In my childhood, I would see hundreds of amazing storytellers in local tea stalls. They would sit there for hours telling all possible and impossible stories. In those tea stalls, they would mostly create fake stories and used to tell them in most believable ways. Some of them would tell fake stories about their rich relatives, some would tell stories about their greatness and fortune. I used to think why they lie but didn’t have the answer ready. When I grew up, I realized why they lie. They lie because sometimes lies comfort our souls. I think growing up among such amazing storytellers might have just pushed the basic human instinct of storytelling in me.

I faintly remember getting a video camera in my hand when I was in high school. It belonged to some of my relatives, I guess. Bit what I clearly remember is my dress and action. That image is planted in my mind so vividly. I was wearing a white shirt with sleeves up and trying to capture the panoramic view of the road in front of my maternal uncle’s house. At one point, one of my cousin came to see what I am doing. And he started to shoot me. I remember I gave a director-like pose with two of my hands framing something. Now I remember it was a pose which I subconsciously copied from one of Satyajit Ray’s famous photograph at work. I didn’t learn filmmaking from any school or any mentor though. I jumped into the water and learnt swimming. In other words, I consider myself to be a lifelong student of world university of mistakes. I learn from my own mistakes.

Are there a lot of filmmakers in Bangladesh including arthouse filmmakers? Are there film schools in Bangladesh? Where do most filmmakers from Bangladesh learn about cinema and filmmaking?

There is no film school in Bangladesh. People mostly learn the craft and art of it by assisting other directors. In early eighties, there was an independent short film movement in Bangladesh. It gave birth to films like The Wheel by Morshedul Islam (Chaka), which has been included in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s favorite 50 films by the way. This movement gave birth filmmaker like Tareque Masud whose 2002 film Clay Bird was in Directors’ Fortnight. Although this movement didn’t go any further but it influenced a newer generation of filmmakers who capitalized on the evolution of digital medium and mushrooming of satellite television in Bangladesh. I actually belong to that generation. We started making short films or fiction films for television channels. Although we worked for TV, our basic intention was to practice the cinematic style of our own. It resulted into a paradigm shift in audience’s taste and filmmakers’ visual style. In the meantime, some of our films went to international festivals like Toronto and Rotterdam. But ever since Busan selected Television as their closing film in 2012, Bangladeshi cinema constantly saw an uptick. Lot of younger filmmakers are now coming out with fresh ideas, dreams, and hope.

Although there is no proper ecosystem to support local talents, I believe our cinema will be able to make a mark in the coming years thanks to the undying spirit of our younger filmmakers.

How do independent Bangladeshi filmmakers finance their films? Are there producers?

Well, financing is big problem. We have a very few financiers who finance in independent films. Government has a funding system which is probably for some special kind of films or people. The way you know the term « producer » is very different than how Bangladeshi industry knows. In Bangladesh, people who finance a film are called producers. And directors mostly work as uncredited producers in those films. So it’s a kind of mess.

To give you an idea of the average budget of my films, the production budget of Television was about 300,000 USD. And the production budget of Saturday Afternoon, which was presented in Busan film festival last year and just received two prizes at Vesoul International Film Festival of Asian Cinema, was 400,000 USD.

How many independent/arthouse films (like yours) are produced every year? How many are released in Bangladesh?

At one point, it was three to four a year. Now it’s down to one or two.

From a global point of view (including commercial films), Bangladesh used to produce about 52 films a year. Now it has come down to 20 films.

Have your movies been released in Bangladesh? If so, how did the audience react?

Yes, all my films have been released in Bangladesh and it mostly enjoyed some kind of following by young audience. However censorship has always been an issue for me. I made seven films so far. Out of seven, five films suffered at the hand of censor board. I now feel it has started making me tired. I hope it doesn’t cripple my spontaneous thought process. But it is really annoying!

In January 2019, the Bangladesh Film Censor Board banned the theatrical release of my latest film, Saturday Afternoon. That decision is actually a mystery to me! After the screening of the film at the censor board, they called me to let me know they appreciated the film. Some of them even gave interviews in the local press, praised the film and mentioned the film would be issued a certificate soon. Two days later, I started to see an online campaign by some Islamic preachers that demanded the film be banned. In 24 hours, those preaching videos were shared thousands of times. They said all false things against the film without even watching the film. Two days later, the censor board called for an unprecedented second screening of the film. After the second screening, they decided not to issue a certificate. We have appealed against the decision, which is still pending.

How would you define Bangladeshi cinema? Is there a specific cultural identity? A specific history/evolution?

Bangladeshi cinema has typically been a copycat of Indian mainstream or Kolkata art house (the Satyajit Ray, Ritwick Ghatak, Mrinal Sen way). There have few exceptions but that’s the general picture. When we started to make films, we defied to follow this. We decided to follow our own hearts. We picked stories from our daily lives. We discarded the traditional stylized acting. We got rid of bookish and fake dialogues. It helped us connect with a big young population but it also angered the establishment. So lot of debate started to surface regarding our use of dialogue, Bengali accent, choice of subjects. However the beautiful part is Bangladeshi cinema has started to be personal. Our films started to reflect our personalities. I think, if we can continue like this and can keep making more films, we will see some kind of collective identity of Bangladeshi cinema.

How would you define your own cinematographic style, your vision or point of view as an auteur?

Well, I want rest it upon the audience and critics. However if I have no other option but to tell something about my cinematic vision or style, I would say I am probably an explorer, an experimenter. I want to experience things in their most uninhibited forms and want my audience to experience my work of art like an explorer. I want my cast to act true and be completely unaware of the audience’s presence.

During the shooting of Saturday Afternoon, most of the cast actually started to live in the zone psychologically. So at one point, they didn’t have to act as they started to respond from their instinct. Among them, the old gentleman, who played the role of Mr. Mojammel Huq, he really got unwell because of the trauma. Once our shooting was over, he was admitted into PG hospital as his blood pressure shot was so high!

You founded Chabial movement, which is considered a Bangladeshi avant-garde cinema movement. Can you tell us more about that?

Chabial is basically my production company. The productions that we made might have influenced a paradigm shift in traditional Bangladeshi visual storytelling to a more personal kind of filmmaking with the use of humor, fantasy, absurdity and emotion. I don’t know whether people hint to this influence when they talk about Chabial. Also I have helped a good number young filmmakers learn the craft of storytelling through on job training. This infused a lot of energy and fresh blood into the industry. Maybe people mean this when they talk about Chabial.

What was the last film you saw in cinema that you really liked?

I know it may sound too mainstream after four historic Oscar wins, for which I am obviously happy, it’s PARASITE! Even if it’s probably not Bong’s best film, the great thing about this film is the sheer smoothness and easy confidence of the director. If the same script were made by another director, there would have been every risk of being too cheesy, too obvious and wishful! Bong Joon-ho’s masterful direction made it a smooth and believable film.

Interview by Françoise Duru

(4 / 5 First time director Gu Xiaogang has accomplished an outstanding feature with both elegance and simplicity that – literally and figuratively – make that three-generation family saga a painting imprinted with gentle poetry and remarkable accuracy while avoiding the pitfalls of formalism.)

(4 / 5 First time director Gu Xiaogang has accomplished an outstanding feature with both elegance and simplicity that – literally and figuratively – make that three-generation family saga a painting imprinted with gentle poetry and remarkable accuracy while avoiding the pitfalls of formalism.)DWELLING IN THE FUCHUN MOUNTAINS

(春江水暖, Chun Jiang Shui Nuan)

A film by Gu Xiaogang

With Qian Youfa, Wang Fengjuan, Zhang Renliang, Zhang Guoying, Sun Zhangjian, Sun Zhangwei, Du Hongjun, Peng Luqi, Zhuang Yi

With Qian Youfa, Wang Fengjuan, Zhang Renliang, Zhang Guoying, Sun Zhangjian, Sun Zhangwei, Du Hongjun, Peng Luqi, Zhuang Yi

2019 – China – Drama – 154 min – 1.85:1 Aspect ratio – 5.1 DTS Sound – Audio: Mandarin and Fuyang dialect

World premiere: May 22, 2019 (Cannes Film Festival)

| Screenplay: |  (4 / 5) (4 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (4 / 5) (4 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (4 / 5) (4 / 5) |

« Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains » (富春山居圖), Gu Xiaogang’s beautiful first feature film, which premiered at Cannes International Critics’ Week in 2019, is first and foremost the title of a Chinese handscroll masterpiece in the « shanshui » (山水) genre, which describes a traditional form of Chinese landscape painting1Traditional Chinese painting can be classified into three categories: figure painting, landscape painting, and flowers and birds painting. featuring mountains and water (rivers and waterfalls) – « shan » (山) means « mountain » and « shui » (水) means « water ».

Shanshui paintings are designed to be viewed from bottom to top as far as hanging scrolls (vertical compositions) are concerned, and from right to left as far as handscrolls (horizontal compositions) are concerned, revealing one scene at a time – as is the case with Huang Gongwang’s painting, which inspired Gu Xiaogang’s film. As each new section is unrolled, the previous scene is rolled up, giving the viewer the feeling of a journey through the landscape, which offers the experience of moving through space and time – the time dimension usually being the privilege of literary or musical expression. Viewing section by section calls for particular kinds of engagement on the part of the viewer moving forward, stopping and going back.

Taoist philosophy strongly influenced the development of the ancient Chinese landscapes as an art form. Thus, Taoism emphasizes that humans are insignificant in the great cosmic flow of nature. Ancient Chinese landscapes depict humans as mere specks and exhibit a great veneration for the forces of nature.

Furthermore, the balance of yin and yang was essential in the design of the landscape painting. Mountains are tall and robust, representing yang, whereas water is soft and flowing, representing yin.

The intrinsic complementarity of mountain and water lied in the featured alternation between full and empty, between inked and white surfaces. It complied with the cosmic yin-yang movement that drove the binary structure of the creative process. Ancient Chinese philosophy emphasizes that true painting must embody not only the form but also the spirit of the subject. The depiction of outward beauty in itself is not enough, as the artist seeks to capture the inner vitality of nature. The outward appearance of a natural phenomenon must be portrayed in tune with its spirit and energy, so realism never was the artist’s ultimate purpose. It’s eventually about the artist’s perception of an inner reality and wholeness.

Shanshui paintings also involve a complicated and rigorous set of requirements for balance, composition, and form. Each painting contains three basic elements, “paths” – always tortuous; may be one or several rivers –, a “threshold” – of a mountain or of heaven –, and the “heart” or focal point – onto which converge all the elements, the heart defining the meaning of the painting.

For director Gu Xiaogang, Chinese and Western aesthetic approaches are very different: « China and the West have their own artistic aesthetics. There is no better or worse, but just differences. Western painting pays attention to express the space, while Chinese traditional landscape painting attempt to play the game of time, in order to archive a sense of universe – eternity of time and infinity of space. To accomplish this, sometimes it strategically sacrifices other elements, as realistic expression of lights and shadows. Just as Huang Gongwang, the painter of Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, he constantly adjusted the focal point of the painting, and constructed various angles into an unified and complete visual experience. The viewers are sometimes situated in the sky, sometimes down to the earth, sometimes into the forest, as they are flowing and tripping. It totally surpasses the shackles of two-dimensional painting.

The way the ancients opened the scroll painting was also from right to left, slowly. More images and further plots are seen little by little only with the rolling. It’s somehow like a film movie.»

It’s by the end of his life that Huang Gongwang (1269–1354) painted « Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains », a handscroll measuring over 22 feet in length. Huang Gongwang is the oldest of the group of Chinese painters later known as the « Four Masters of the Yuan dynasty » (1206-1368).

The Yuan dynasty (元四家), aka the Mongol dynasty, was the first non-Han Chinese dynasty to rule all of China from 1279 until 1368. It was founded by Kubilai Khan, the grandson of Gengis Khan.

The Mongols conquest enforces a bitter new political reality consequent to China, which for the first time was under foreign rule. As the Mongols had no tradition of employing scholars as administrators, many Chinese scholars and artists were excluded from the Yuan court. Many of these elites turned to private retreats for sanctuary and turned their estates into places for literary and cultural gatherings. They identified themselves as literati through their poetry, calligraphy, and painting and used painting as a vehicle for self-expression and no longer took truth to nature as their goal.

This was the context for Huang Gongwang’s masterpiece – considered influential for the development of artistic foundations for later literari landscape painters in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644)1912) dynasties.

« Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains » changed owners multiple times and ended up in the hands of an art collector who, on his deathbed in 1650, decided to burn it so he could still savor it in the afterlife. Fortunately a family member saved it but the painting had already been torn in two parts. The first part, known as « The Remaining Mountain » (剩山圖), is 51.4 centimeters long and now an important work in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum collection in Hangzhou. The latter section, called « The Master Wuyong Scroll » (無用師卷), composed of six joined pieces of paper and measuring 636.9 centimeters long, entered the Qing imperial collection in 1746 and ranks as a national treasure of the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

In 2011, these two parts of the masterpiece landscape were reunited for the first time in 360 years when they were displayed together at an exhibition at the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

Watch the English-subtitled video produced by the National Palace Museum below to learn more:

Tonglao S. Epinal

Tonglao S. Epinal is a photographer and video artist, who contributed to several magazines as a freelance writer and frequently travels to South East Asia for her works and research. She is currently working on a documentary feature that explores the relationship between the legacy of Soviet cinema and the paradox of censorship in the development of Asian cinema from 1956 to 1986.

Bibliography

Montagnes et eaux. La culture du Shanshui, Yolaine Escande, Paris, Hermann, 2005.

Das aguas da montanha à paisagem, Adriana Verissimo Serrão (dir.), Filosofia e arquitectura da paisagem, Centro de filosofia da Universidade de Lisboa, 2012, trad. Augustin Berque.

Chinese Shan Shui Painting Through the Yuan Dynasty, Mike Cai, The Epoch Times, 14/01/2019.

Premiers éléments d’un petit dictionnaire de la peinture chinoise, in catalogue « Trésors du Musée national du Palais, Taipei » from October 22, 1998 to January 25, 1999 at Grand Palais, Simon Leys.

Being in the Dry Zen Landscape, Robert Wicks, The Journal of Aesthetic Education Volume 38, Number 1, Spring 2004.

Huang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, Hung Chen, Khan Academy, 2016.

(3.3 / 5 Like it or not, Takashi Miike is a master at blending genres from yakuza films to gory pulp and slapstick romance: FIRST LOVE is a deranged, hilarious, frantic, exhilarating Long Day's Journey into Night!)

(3.3 / 5 Like it or not, Takashi Miike is a master at blending genres from yakuza films to gory pulp and slapstick romance: FIRST LOVE is a deranged, hilarious, frantic, exhilarating Long Day's Journey into Night!)FIRST LOVE

(初恋, Hatsukoi)

A film by Takashi Miike

With Masataka Kubota, Nao Ōmori, Shōta Sometani, Sakurako Konishi, Becky

With Masataka Kubota, Nao Ōmori, Shōta Sometani, Sakurako Konishi, Becky

2019 – Japan/UK – Pulp noir / Black comedy / Romance – 108 min – Aspect ratio 1.85:1 – 5.1 Sound – Audio: Japanese

World premiere: May 17, 2019 (Cannes Film Festival, Directors’ Fortnight)

| Screenplay: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

(3.3 / 5 Halfway between film noir and a mystic journey, HONEYGIVER AMONG THE DOGS is a strange and riveting incursion into Bhutanese culture.)

(3.3 / 5 Halfway between film noir and a mystic journey, HONEYGIVER AMONG THE DOGS is a strange and riveting incursion into Bhutanese culture.)HONEYGIVER AMONG THE DOGS

(Munmo Tashi Khyidron)

A film by Dechen Roder

With Jamyang Jamtsho Wangchuk, Sonam Tashi Choden

With Jamyang Jamtsho Wangchuk, Sonam Tashi Choden

2016 – Bhutan – Mystic film noir – 118 min – Aspect ratio 1.85:1 – 5.1 Sound – Audio: Dzongkha

French theatrical release: October 24, 2018

Watch the film on VOD here

| Screenplay: |  (3.0 / 5) (3.0 / 5) |

| Mise en scène: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

| Interpretation: |  (3.5 / 5) (3.5 / 5) |

Thinley Choden is a producer and social entrepreneur from Bhutan. Her first film project was the Emmy Award winning documentary Bhutan: Taking the Middle Path to Happiness in 2007, on which she worked as an advisor. In 2008 she successfully established READ Bhutan – a non-profit organization that is part of the READ Global network (READ for Rural Education And Development) – , which she headed until 2014, and produced a series of short documentaries directed by Dechen Roder. In 2015, Choden collaborated on Dechen Roder’s first feature film Honeygiver Among the Dogs – which premiered at Berlin Film Festival in 2017 – assisting in fundraising, publicity and taking the role of an investor and presenter of the film. She is currently co-producing Roder’s second feature film, I, the Song.

You are a film producer in Bhutan. Can you tell us how you ended up as a producer?

My journey towards film producing is actually a combination of coincidences. It just came organically, mainly because of my friend Dechen Roder –whose films I’m producing. When I first started my non-profit organization in 2008, she made promotional videos for my organization. And before that, in 2003, when I was in Hawaii, I helped a friend a mine –a documentary filmmaker and a photographer living in Hawaii–, who wanted to make a documentary on Bhutan about the development of the Gross National Happiness philosophy. So my path toward film producing was not a continuous journey. But how it came together was with Dechen Roder. With her first feature film, HONEY GIVER AMONG THE DOGS, I came in as a gap funder. I wasn’t fully on board as a producer but still helped her here and there through my involvement in the film… With her second feature, I, THE SONG, she asked me to come on board to help her as a producer. and that’s what I’m doing… although I know I don’t have the full experience of producing a film. But in Bhutan we don’t have production houses nor an actual film production culture: noone becomes a film producer by design. The director is usually the producer, the financier and everything –all roles in one. Most are learning on the job. For I, THE SONG, Dechen is the director and writer of the film but also the coproducer. As far as I’m concerned, I got into film production because Dechen asked me. I had a lot of experience in fundraising thanks to my other activities and I developed a network too. My entrepreneur background did help as I was able to jump in without having prior technical qualities of film production. The stake is more about how quickly you learn and adapt to a new environment and handle situations.

Are there specific funds in Bhutan or do you resort to private financing only ?

It’s private financing only. We don’t have government funding or film funds in Bhutan. Even for commercial films, you must either find financiers or just get a bank loan. It’s very easy to recoup your money as far as commercial mainstream movies are concerned though. Although our population is very small, there is a strong demand for local content –local mainstream films, that is.