“Radical self-love and acceptance” – all the rage in western societies- hasn’t quite reached South Korea. A Korean’s self-worth is first and foremost defined by others’ judgment, in turn directly determined by one’s Suneung results. This national exam can make or break a reputation and a bad score can become a lifelong, sometimes fatal, stigma. Bong Joon-Ho gets down and dirty in PARASITE and taunts – through the characters’ outrageous attitudes which lead to a downward spiral – the weight of this ‘rite of passage’. In a more matter-of-fact way, Marie-Orange Rivé-Lasan and Jin-ok Kim reveal the underpinnings of the Suneung, which produces extreme and sometimes-bleak consequences.

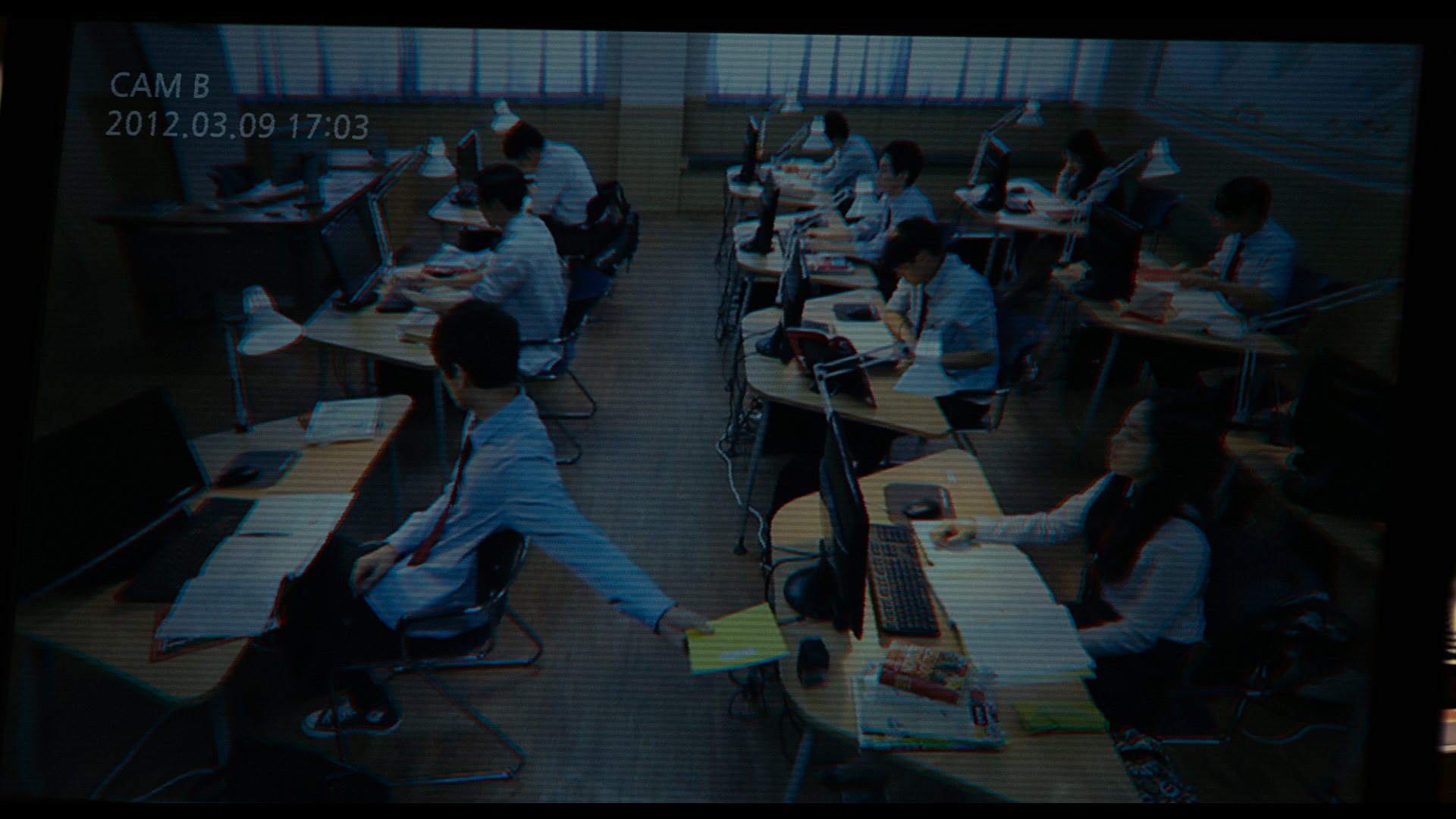

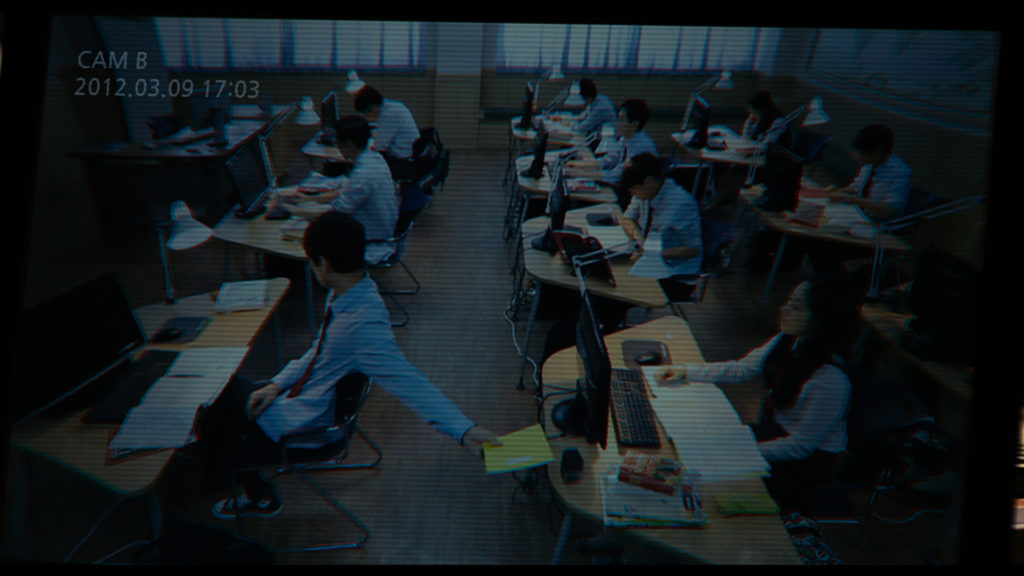

The term « Suneung » is an abbreviation of the expression « suhak neungnyôk sihôm » which literally translates to « aptitude studies test », the unavoidable end of studies exam preceding university in South Korea. This decisive test doesn’t only attest to a specific level of competence, it also (and especially) generates a national ranking of all the candidates. According to this ranking, the candidates may apply to different universities. Universities are nationally classified: the higher they rank the more candidates they can potentially attract. The three most sought after universities are referred to by the diminutive “SKY”, which stands for “Seoul National University”, “Korea University”, and “Yonsei University”. Getting into one of these universities gives access to a whole network of connections close to economic and political powers. It is a factor of social promotion and mobility, of highly-remunerated job opportunities and the key to ‘good’ marriages. Middle class families prepare their children a long time in advance (as early as kindergarten), through expensive extra-curricular lessons provided by private tutoring establishments. Known as “hagwons” these establishments (all 100,000 of them) generate approximately 2% of the country’s GDP and attract more than three out of four students. Indeed, it ha become commonplace nowadays for families to sacrifice everything in order to finance the studies of their children, spending sometimes up to a thousand euros every month per child until the end of high school, with the hope of obtaining the best possible ranking in the “Suneung”. Moreover, university fees constitute a significant expense, even in the case of non-private universities.

The Montreal Centre for International Studies (CERIUM in French) reports that each year, on the day of this exam, the whole country holds its breath: most offices and administrations close or open later in order not to interfere with the arrival at exam centers, late students are brought by the police and the entire airspace is closed off during the oral comprehension test.

Traditionally, Confucian culture is centered on education, as it is the case in China and Japan. In South Korea, the effective business of education coupled with parents’ obsession over their children’s success – leading them to consider the exorbitant amounts spent in education as rational investments for their future economic situation – amount to children being under an enormous pressure (they study on average 50 hours per week which is 16 times more than the average in OECD countries). The substantial decrease in birth rate – the fertility rate, 1.15 children per woman, remains one of the weakest in the OECD – is directly linked to this situation. It has become inconceivable to think of making children without being capable of undertaking the “socially necessary” expenses “good parents” have to make. The demographic consequences are very real: South Korean society has been deeply transformed by the aging of its population and the inevitable immigration of foreign labor.

The demands of this super-technological consumerist society have led to abuses, especially in regards to the younger generation, robbed of its youth and left psychologically strained. The extremely high suicide rate of this category (ahead of Japan’s) attests to this, alongside the consequential spread of new protest movements.

There are a number of private universities that, for the most part, don’t even guarantee the desired social status and produce generations of unemployed frustrated graduates – marginalized and socially discredited.

To sum things up, succeeding at the “Suneung” is succeeding at life!….and failing it, is hell…

Marie-Orange Rivé-Lasan and Eunsil Yim

Marie-Orange Rivé-Lasan is a historian and lecturer at Paris Diderot University (UPD)/UMR 8173 China, Korea, Japan (EHESS-CNRS-UPD) and Eunsil Yim is an anthropologist, UMR 8173 China, Korea, Japan (EHESS-CNRS-UPD)