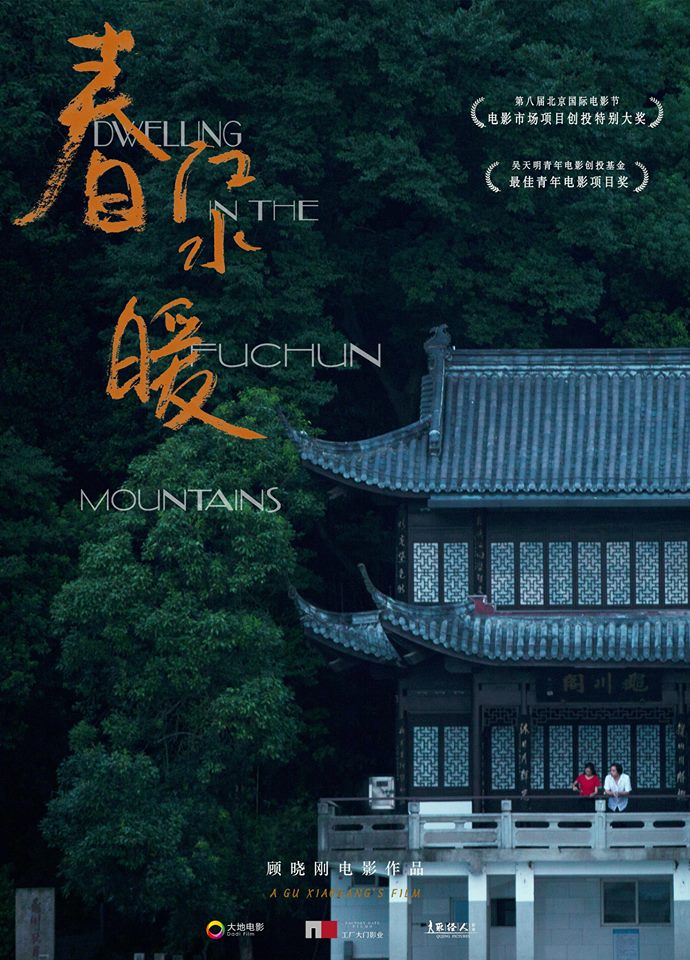

« Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains » (富春山居圖), Gu Xiaogang’s beautiful first feature film, which premiered at Cannes International Critics’ Week in 2019, is first and foremost the title of a Chinese handscroll masterpiece in the « shanshui » (山水) genre, which describes a traditional form of Chinese landscape painting1Traditional Chinese painting can be classified into three categories: figure painting, landscape painting, and flowers and birds painting. featuring mountains and water (rivers and waterfalls) – « shan » (山) means « mountain » and « shui » (水) means « water ».

Shanshui paintings are designed to be viewed from bottom to top as far as hanging scrolls (vertical compositions) are concerned, and from right to left as far as handscrolls (horizontal compositions) are concerned, revealing one scene at a time – as is the case with Huang Gongwang’s painting, which inspired Gu Xiaogang’s film. As each new section is unrolled, the previous scene is rolled up, giving the viewer the feeling of a journey through the landscape, which offers the experience of moving through space and time – the time dimension usually being the privilege of literary or musical expression. Viewing section by section calls for particular kinds of engagement on the part of the viewer moving forward, stopping and going back.

Taoist philosophy strongly influenced the development of the ancient Chinese landscapes as an art form. Thus, Taoism emphasizes that humans are insignificant in the great cosmic flow of nature. Ancient Chinese landscapes depict humans as mere specks and exhibit a great veneration for the forces of nature.

Furthermore, the balance of yin and yang was essential in the design of the landscape painting. Mountains are tall and robust, representing yang, whereas water is soft and flowing, representing yin.

The intrinsic complementarity of mountain and water lied in the featured alternation between full and empty, between inked and white surfaces. It complied with the cosmic yin-yang movement that drove the binary structure of the creative process. Ancient Chinese philosophy emphasizes that true painting must embody not only the form but also the spirit of the subject. The depiction of outward beauty in itself is not enough, as the artist seeks to capture the inner vitality of nature. The outward appearance of a natural phenomenon must be portrayed in tune with its spirit and energy, so realism never was the artist’s ultimate purpose. It’s eventually about the artist’s perception of an inner reality and wholeness.

Shanshui paintings also involve a complicated and rigorous set of requirements for balance, composition, and form. Each painting contains three basic elements, “paths” – always tortuous; may be one or several rivers –, a “threshold” – of a mountain or of heaven –, and the “heart” or focal point – onto which converge all the elements, the heart defining the meaning of the painting.

For director Gu Xiaogang, Chinese and Western aesthetic approaches are very different: « China and the West have their own artistic aesthetics. There is no better or worse, but just differences. Western painting pays attention to express the space, while Chinese traditional landscape painting attempt to play the game of time, in order to archive a sense of universe – eternity of time and infinity of space. To accomplish this, sometimes it strategically sacrifices other elements, as realistic expression of lights and shadows. Just as Huang Gongwang, the painter of Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, he constantly adjusted the focal point of the painting, and constructed various angles into an unified and complete visual experience. The viewers are sometimes situated in the sky, sometimes down to the earth, sometimes into the forest, as they are flowing and tripping. It totally surpasses the shackles of two-dimensional painting.

The way the ancients opened the scroll painting was also from right to left, slowly. More images and further plots are seen little by little only with the rolling. It’s somehow like a film movie.»

It’s by the end of his life that Huang Gongwang (1269–1354) painted « Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains », a handscroll measuring over 22 feet in length. Huang Gongwang is the oldest of the group of Chinese painters later known as the « Four Masters of the Yuan dynasty » (1206-1368).

The Yuan dynasty (元四家), aka the Mongol dynasty, was the first non-Han Chinese dynasty to rule all of China from 1279 until 1368. It was founded by Kubilai Khan, the grandson of Gengis Khan.

The Mongols conquest enforces a bitter new political reality consequent to China, which for the first time was under foreign rule. As the Mongols had no tradition of employing scholars as administrators, many Chinese scholars and artists were excluded from the Yuan court. Many of these elites turned to private retreats for sanctuary and turned their estates into places for literary and cultural gatherings. They identified themselves as literati through their poetry, calligraphy, and painting and used painting as a vehicle for self-expression and no longer took truth to nature as their goal.

This was the context for Huang Gongwang’s masterpiece – considered influential for the development of artistic foundations for later literari landscape painters in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644)1912) dynasties.

« Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains » changed owners multiple times and ended up in the hands of an art collector who, on his deathbed in 1650, decided to burn it so he could still savor it in the afterlife. Fortunately a family member saved it but the painting had already been torn in two parts. The first part, known as « The Remaining Mountain » (剩山圖), is 51.4 centimeters long and now an important work in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum collection in Hangzhou. The latter section, called « The Master Wuyong Scroll » (無用師卷), composed of six joined pieces of paper and measuring 636.9 centimeters long, entered the Qing imperial collection in 1746 and ranks as a national treasure of the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

In 2011, these two parts of the masterpiece landscape were reunited for the first time in 360 years when they were displayed together at an exhibition at the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

Watch the English-subtitled video produced by the National Palace Museum below to learn more:

Tonglao S. Epinal

Tonglao S. Epinal is a photographer and video artist, who contributed to several magazines as a freelance writer and frequently travels to South East Asia for her works and research. She is currently working on a documentary feature that explores the relationship between the legacy of Soviet cinema and the paradox of censorship in the development of Asian cinema from 1956 to 1986.

Bibliography

Montagnes et eaux. La culture du Shanshui, Yolaine Escande, Paris, Hermann, 2005.

Das aguas da montanha à paisagem, Adriana Verissimo Serrão (dir.), Filosofia e arquitectura da paisagem, Centro de filosofia da Universidade de Lisboa, 2012, trad. Augustin Berque.

Chinese Shan Shui Painting Through the Yuan Dynasty, Mike Cai, The Epoch Times, 14/01/2019.

Premiers éléments d’un petit dictionnaire de la peinture chinoise, in catalogue « Trésors du Musée national du Palais, Taipei » from October 22, 1998 to January 25, 1999 at Grand Palais, Simon Leys.

Being in the Dry Zen Landscape, Robert Wicks, The Journal of Aesthetic Education Volume 38, Number 1, Spring 2004.

Huang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, Hung Chen, Khan Academy, 2016.