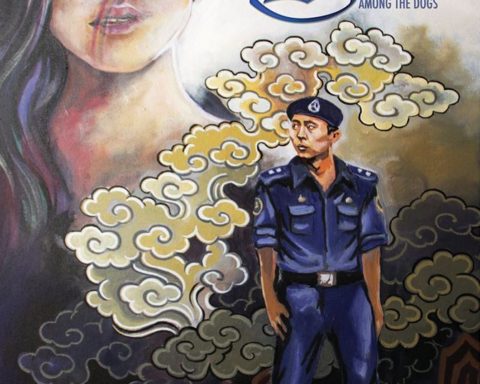

Thinley Choden is a producer and social entrepreneur from Bhutan. Her first film project was the Emmy Award winning documentary Bhutan: Taking the Middle Path to Happiness in 2007, on which she worked as an advisor. In 2008 she successfully established READ Bhutan – a non-profit organization that is part of the READ Global network (READ for Rural Education And Development) – , which she headed until 2014, and produced a series of short documentaries directed by Dechen Roder. In 2015, Choden collaborated on Dechen Roder’s first feature film Honeygiver Among the Dogs – which premiered at Berlin Film Festival in 2017 – assisting in fundraising, publicity and taking the role of an investor and presenter of the film. She is currently co-producing Roder’s second feature film, I, the Song.

You are a film producer in Bhutan. Can you tell us how you ended up as a producer?

My journey towards film producing is actually a combination of coincidences. It just came organically, mainly because of my friend Dechen Roder –whose films I’m producing. When I first started my non-profit organization in 2008, she made promotional videos for my organization. And before that, in 2003, when I was in Hawaii, I helped a friend a mine –a documentary filmmaker and a photographer living in Hawaii–, who wanted to make a documentary on Bhutan about the development of the Gross National Happiness philosophy. So my path toward film producing was not a continuous journey. But how it came together was with Dechen Roder. With her first feature film, HONEY GIVER AMONG THE DOGS, I came in as a gap funder. I wasn’t fully on board as a producer but still helped her here and there through my involvement in the film… With her second feature, I, THE SONG, she asked me to come on board to help her as a producer. and that’s what I’m doing… although I know I don’t have the full experience of producing a film. But in Bhutan we don’t have production houses nor an actual film production culture: noone becomes a film producer by design. The director is usually the producer, the financier and everything –all roles in one. Most are learning on the job. For I, THE SONG, Dechen is the director and writer of the film but also the coproducer. As far as I’m concerned, I got into film production because Dechen asked me. I had a lot of experience in fundraising thanks to my other activities and I developed a network too. My entrepreneur background did help as I was able to jump in without having prior technical qualities of film production. The stake is more about how quickly you learn and adapt to a new environment and handle situations.

Are there specific funds in Bhutan or do you resort to private financing only ?

It’s private financing only. We don’t have government funding or film funds in Bhutan. Even for commercial films, you must either find financiers or just get a bank loan. It’s very easy to recoup your money as far as commercial mainstream movies are concerned though. Although our population is very small, there is a strong demand for local content –local mainstream films, that is.

For I, THE SONG (estimate budget: USD 390,000), we’re applying for grants –especially from organizations like the UN and other organizations that are either gender-related or women empowerment-related, or also deal with media literacy because I, THE SONG is very much about digital media exploitation… We look at different angles of how we can link the issues of the film and we apply for grants from those organizations. We also contact businesses and offer exposure to them through the film poster or the film credits since it is screened at international film festivals and in Bhutan as well. That’s how we can get sponsors and the funding in Bhutan.

How did you meet Dechen Roder ?

Dechen and I went to the same high school. We’ve known each other since we were teenagers. We went to the same boarding school in India. Then we both went to college in the US –but she went to film school whereas I studied economics and international relations. Not in the same city nor in the same state though. Then we both came back to Bhutan after college and that’s when we reconnected again.

How would you describe Dechen Roder’s cinema?

Dechen is a very noir-style filmmaker. She has a liking for thrillers and mystery. She likes to tell stories in a very complex way so that the audience needs to engage with the cinematographic universe she creates in order to fully embrace it. Her films have a philosophical aspect that mingles traditions and spirituality, which are so important in Bhutan. You can not ignore that in the modern landscape. Her films are very… female-centric too –I tend to stay away from using the word ‘feminist’ because I think there are very subjective connotations depending on who you talk to [laughs]. Her stories are always told from the perspective of the women whatever the story context.

Is it unusual in Bhutan’s culture ? Is it a patriarchal society ?

We have a matrimonial practice. Property, everything, goes through the mother to the daughter. When you marry, the husband moves into the daughter’s house. The women inherit property.

In our region, women are actually quite empowered and respected: every family would rather have daughters than sons! Women have, if not equal, more moral rights. From that sense, it’s very progressive.

But as far as cultural practice is concerned, in terms of private space vs public space consideration for instance –with respect to women in leadership, women involved in businesses, filmmaking, making decisions at a national level and son on–, you don’t see many women: it’s mainly male-dominated. My own theory is that Bhutan’s education started only in the 60s. Until then, the only way to get education was to join the clergy –that is, become a monk or a nun. Until then, people worked the land, looked after the land. The land looked after you. You didn’t really need to go beyond that. You know, Bhutan was never colonized. We lived in our own culture and time frame. We have always been sheltered from global trends whatsoever. In the 60s, when the third king, Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, started to encourage modern education practice, a lot of parents didn’t know what education was, there were no schools in Bhutan. The government recruited students to be sent to India to get education. Still now there are still a lot of kids going to boarding schools there. For parents who never traveled beyond a village let alone outside Bhutan, they didn’t know what education meant, and sending kids abroad was a big threat. Daughters were not expendable, they were precious. So they hid their daughters and would send their sons instead. Daughters needed to stay because they needed to look after the family property. So in the process, a lot of girls didn’t go to school. My mother didn’t actually go to school. My grand-mother hid my mother in the granary as the government people went from house to house to recruit students!

Over the years, as Bhutan was modernizing and bureaucracy became more and more educated –the minimum these days is to have a college degree–, women were unable to participate to the public space because they didn’t have the required education/qualification. Only men are seen in the public space. So over the years, the public has been so used to seeing men in leadership positions, they tend to think men do a better job. So it all started with good intentions from the parents, but now it has backfired –good intentions may lead to bad income… It has taken root in the patriarchal public narrative and expectations so that we have a matrimonial practice but very patriarchal attitudes and expectations. Also it is true that in the rural areas, you really have to choose who to keep at home, who is more helpful at home. Normally it’s the girls –they look after the family and the house… With the new generations though, women are just as active in the home space as in the public space. Now there are more and more girls and women that do far better than boys and men. There are very few but when there are, they do far better than men –and not just in Bhutan from my point of view! [laughs]

Are there a lot of women filmmakers in Bhutan?

Very few! There are about 5 female directors (short and feature films). Dechen is the second and currently only female director making international art house films. It’s a pretty male-dominated industry for the reasons mentioned before. There are a lot of women in acting but not directing. Dechen is the only one who made her name on both the national and international scene.

So I guess there are not a lot of women producers in Bhutan either?

No… [laughs] Also in Bhutan when one thinks of a producer, they just think of someone shelling out money. They’ll target someone who has the money, and that person will just give the money and not be involved in the creative process. Which is a definition in itself. But not in the way I work with Dechen.

Do you plan to produce films by other filmmakers from Bhutan or from other countries later on?

Right now, I see myself helping Dechen make more films in the future. But If I see someone come up with as much talent as Dechen, then why not? I’m not interested in mainstream commercial films though because there are enough of them out there and they are not necessarily content-driven. It’s more market-driven –not judging that though, it’s fine. I’m just more interested in more arthouse creative processes. Also, I keep telling Dechen once we get to the point we’re both comfortable in terms of our confidence in all this, it would be very helpful to launch a producer’s workshop in Bhutan. Not many people understand what the true meaning and true work of a producer is –and actually even that of a director or a screenwriter!

Are Dechen Roder’s films considered arthouse in Bhutan ? How does the market/audience react to her movies ?

They are considered arthouse. Mainstream Bhutanese films are very Bollywood-like: songs, dance, drama, love, cries etc… [laughs] Her films are considered independent.

How does the market react ? Not so well… [laughs] We are a country of 750,000 people. Even if each person buys a ticket –which is not realistic with respect to the babies, the elderly, the people living in the rural areas–, the market is very small to begin with. Our generation appreciates her films better. But my mother’s generation: they’re not impressed by the aesthetics, the picture frame, the cinematographic style etc. They understand the story but don’t see the point, they want to be entertained… Again, I think it has to do with education, which the previous generations didn’t have access to.

How many movie theaters/screens are there in Bhutan ?

There are 5 actual theaters in entire Bhutan. As for the rest, we don’t really have real cinemas. We have screens. We usually hire simple halls to screen movies: we just hire a hall and put a screen up. There are 20 districts. In each district, there are about 5 screens per district. So there may be about 100 screens in total –mostly single-screen ‘cinemas’ or maybe with 2 screens max. A lot of the screens are all individually and privately-owned. In a way, it’s democratized: there are no multiplexes nor franchises. And it’s a good business because films compete to find space.

For HONEYGIVER AMONG THE DOGS, it was so difficult to get screens. We only had morning times and could only book the theater for ten days. Mainstream films usually book screens for one month. The minimum is 2 weeks but if they think it can do well, they book it for one month. When we come in, whatever space we can get, we squeeze in. And in Bhutan, you have to do everything: you book the theater, you pay the owner uprfont, then marketing, publicity, everything, is done by ourselves. We sit at the ticket counter, we sell the tickets. We do everything!

Sometimes we recoup the costs, sometimes we don’t, sometimes we make a profit.

If you own a theater, you don’t have to do anything because the director has to do everything! So owning and running a theater in Bhutan is definitely a good business!

How many films are produced and released every year in Bhutan ?

On a yearly basis, I’d say 20 films are produced and released –with 95% if them being mainstream films. In addition, maybe one or two international arthouse films are released.

Are there any film critics in Bhutan ?

No, there aren’t. We get ‘reviews’ but those are rather news coverage. Facts. Not actual film reviews.

How did the international audience react to HONEYGIVER AMONG THE DOGS?

Dechen’s first feature film was released in France, Belgium, Poland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and traveled abroad to many international festivals and had special screenings too –in Berlin (where the film premiered), Singapore, Bangkok, India, Washington DC…

The international audience reacted really well to the movie although there are differences in the cultural perception of a film: Europeans certainly appreciated the film more than Americans did. I think it’s a question of culture and sensibility. Also, people who are predisposed to certain Buddhist philosophy and views embraced the film far better than people who did not necessarily have that kind of background or knowledge.

What are the fundamental values promoted by Bhutanese culture?

Our values are very much driven by Buddhist philosophy. In everything we do, there’s a lot of emphasis on impermanence, karma –if you do something bad, it will come back to you. What you do today, it will maybe not come back today but it will come back to you sooner or later. It’s also about birth and rebirth. Family is very important too. It’s a very strong unit of society.

One thing about Bhutan is there’s very little criminality too. We do have crimes –like everywhere– but it’s not rampant and random, we never have mass shootings for instance.

Maybe the fact that we never were colonized plays a role: we never suffered from the historical damages that colonized countries struggle with –both politically and culturally. In that sense, we are lucky and blessed. Also it has a lot to do with our leadership. We are still a monarchy but we have become a parliamentary democracy in 2008. Until then, the way our kings designed the rules and ruled the country was very benevolent and thoughtful. For instance, every citizen in Bhutan has land. If you don’t, the King will give you one, you are entitled a land, so that technically noone is landless. Still, of course there is poverty. We don’t have beggars or people sleeping in the streets though. It’s a different definition of poverty: it’s defined by how rural you are. You can be cut out of everything, live in the mountains, in a shack. You don’t have shoes, you don’t have electricity or running water. That is poverty in Bhutan. But even if you live in those rural areas, you’d still get help from the government, say at least once every three months. Having said that, urban poverty is a growing phenomenon too these days because the cost of living keeps increasing. So you have to live in tiny apartments, sometimes sharing with 5 or 6 people. Still, it’s not as bad as in other neighbor countries…

How do you see what goes on in other countries? Is the outside world going crazy ?

Who am I to judge? But yes, the world is going through crazy times… [laughs] More seriously speaking, I think It’s about ego and ignorance. Ego of the leaders and ignorance of the followers. Ignorance because of the lack of education (although you can still reach leadership these days while ignorant!). So it’s a failure of institutions, it’s a failure of democracy. What is the right form of governance is obviously the million dollar question!

Actually in Bhutan, people didn’t want democracy. But the King wanted to introduce democracy. He was willing to give up his powers. His reasoning was: Bhutan is changing, we are entering in a new modern era, people are getting educated, we have a lot of interactions with the world. As much as democracy is imperfect, it should be the system for the future. He thought: I can speak for myself and for my son but I can not speak for future kings. It’s very dangerous to have absolute power in one hand. Who knows what can come next?

The reason why people in Bhutan didn’t want democracy is because it creates a lot of divisions in the society, families etc. When there is democracy, you have to take sides, you have to campaign and therefore point at what’s going wrong. It arouses conflicts and breaks harmony. Now we are getting used to it, with short-termism remaining the only concern though since every commitment/pledge/promise is based upon election stakes like in every democracy. We don’t have that in monarchies… So what’s crucial are the institutions, the checks and balances.

Interview by Françoise Duru